This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

Listing on Vietnam Wall sought for troops killed in 1962 plane crash

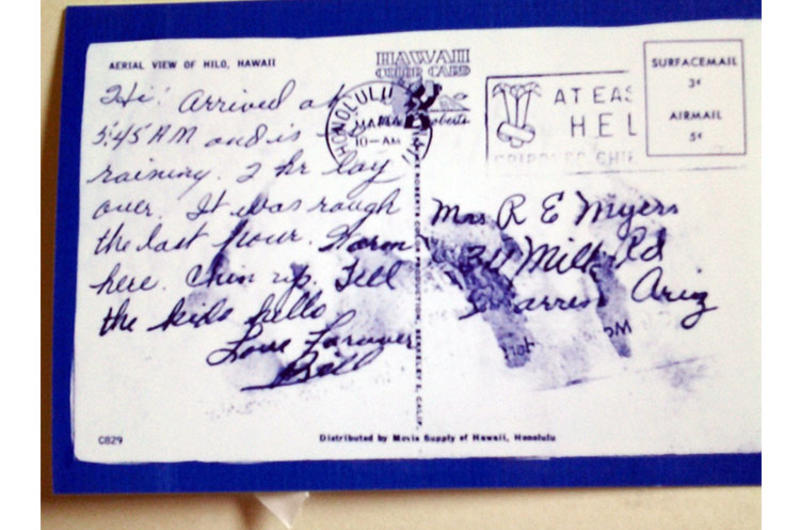

''Tell the kids hello. Love forever.'' Army Sfc. Raymond "Bill" Myers sent this postcard to his family in Hawaii on stopover while on Flying Tiger Line Flight 739. The plane disappeared mysteriously on March 16, 1962 somewhere between Guam and the Philippines on its way to Vietnam before hostilities had officially broken out.

By Matthew M. Burke | Stars and Stripes July 24, 2013

Before departing for Vietnam 51 years ago, Army Sgt. 1st Class Raymond “Bill” Myers left behind his ID, dog tags and a gold ring he had never taken off before. He told his brother-in-law that he had a bad feeling about the mission and didn’t think he would be coming home. He asked him to watch over his wife and children after he was gone.

Myers then boarded a military-chartered Flying Tiger Airline Lockheed Super Constellation aircraft at Travis Air Force Base in California. After several stops, the plane disappeared over the Pacific and the 93 American soldiers, three South Vietnamese military men and 11 crewmembers onboard were never heard from again. They were declared dead less than two months later.

Myers’ son, Tommy Joe — like the families of the other lost Americans — has no answers about his father’s fate. Adding to that pain is how his father and the others have been forgotten. Their names are not on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., and no government agencies — Army, Air Force, Defense Department, National Archives, State Department, CIA — admit to possessing records related to the soldiers and their mission. None could provide Stars and Stripes with a list of the deceased, although they are mentioned in a Civil Aeronautics Board crash report from 1962.

A petition has been launched to get the names added to the wall. Proponents face an uphill battle and need to prove that the plane was headed to Vietnam for a combat mission — which has been impossible without documentation — or through the special intervention of elected officials.

“They were flying into harm’s way,” said Frank Allen, the Massachusetts man who started the change.org petition in October. Allen is related to one of the men, Sgt. Howard Gallipeau Jr., by marriage. “Had they survived and landed, they might have died under different circumstances. The military treats it like a car accident. They should be honored for what they did.”

Allen’s petition calls for 1,000 signatures, although they are hoping for many more. The petition will be sent to Defense Department officials after it closes in October.

Tommy Joe Myers said after years of being turned away and threatened when pressing for answers and recognition, he has lost all hope.

“It’s hurtful that they won’t put these guys’ names on the wall,” he said. “People need to know what these guys sacrificed. Just give them the same courtesy and respect other guys have gotten.”

A few good men

In early 1962, the U.S. was slowly ramping up involvement in Vietnam, according to editions of Pacific Stars and Stripes from the time. Known military operations were limited mostly to advising the South Vietnamese, and ferrying troops into battle and limited engagements with communist forces when fired upon.

The men on Flight 739 appear to have been hand-picked for the mission; they came from bases across the country, according to Vietnam veteran and retired Marine Bruce Swander, who has spent the last 10 years researching the flight in an effort to get their names added to the wall. He said his research indicates they were advisers trained in communications and not Special Forces.

Pacific Stars and Stripes reported after the plane disappeared that the men were trained jungle troops.

Myers was an all-American boy, according to his son. He grew up in Carterville, Ill., with Steve McQueen good looks and piercing blue eyes. He played minor league baseball in the St. Louis Cardinals organization and commanded attention when he entered the room. But his real passion was military service.

Myers was listed as a supply sergeant in the heavily redacted file his son received upon filing a Freedom of Information Act request several years ago, but he could also speak a multitude of languages. He was a veteran of World War II and had been wounded during two combat tours in Korea.

Myers received his orders to head to Vietnam on March 13, 1962, according to a copy of the orders obtained by Stars and Stripes. The next morning he would be on the ill-fated Military Air Transport Service chartered Flying Tiger Line Flight 739.

As was the case with Myers, Spc. 4 Roger Oliver’s family put a headstone in the ground in his hometown after the plane disappeared. Oliver, from Victory, Wis., was “very studious,” and he joined the Army and was trained in communications, according to his sister, Gloria Oliver Warmuth.

He also told his father that he wouldn’t be coming home from the mission and asked him to take care of his pregnant wife and baby after he was gone. His daughter was born later that year.

“He said, ‘I won’t be back from this,’ ” Oliver’s daughter, Kristina Hoge, told Stars and Stripes. “My grandfather told him, ‘You’ll be fine.’ I think it haunted my grandfather.”

Hoge said over the years she was told by her father’s friends that he was involved in “black ops.” A condolence letter from his commanding officer at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., states that he worked in the Film Library Division there. Her mother thought he was going to Vietnam to make a training film.

Army photos of Sgt. Howard Gallipeau Jr. from Korea show the communications specialist relaying fire instructions over a field radio from “no man’s land” during fighting. He would be wounded in action, have surgery and re-enlist. He was tough but warmhearted, his son, Howard Gallipeau III, told Stars and Stripes.

Eerily, the sergeant too told his wife he would not be coming back alive.

“Before he left, he said, ‘I don’t think I’m going to be coming home from this one,’ ” his son said. “My mom tried to talk him out of going but he said. ‘I have to serve my country.’ ”

The three families contacted by Stars and Stripes said they didn’t know each other and hadn’t shared their stories among themselves.

Flight 739

Flight 739 left Travis Air Force Base on March 14, 1962, with a destination of Saigon, according to a copy of the 1962 Civil Aeronautics Board crash report obtained by Stars and Stripes. No cargo other than passengers, crewmembers and their belongings was reported. U.S. Army Security Service checked all passengers including the unknown foreign nationals.

The flight successfully stopped for refueling in Honolulu, where minor maintenance was performed on the engine ignition systems before they departed for Wake Island, the report said. They arrived at Wake, where maintenance was once again performed before heading to Guam. They arrived at Guam with no reported problems.

“There were no mechanical discrepancies reported and no maintenance was required,” the report said.

After a short layover, they were off again to Clark Air Base, Philippine Islands. They contacted control several times during their flight, and no disturbances or issues were reported.

They were last heard from just after midnight March 16, 1962, 270 miles west of Guam.

Shortly after, the flight stopped answering radio transmissions, the report said. They were never heard from again.

Search-and-rescue operations were launched from Guam and the Philippines within hours, the report said. A Liberian-flagged Standard Oil of California super tanker and its Italian crew reported seeing a midair explosion in the area where Flight 739 should have been.

“It was recalled that a vapor trail, or some phenomenon resembling a vapor trail, was first observed overhead and slightly to the north of the tanker and moving in an east to west direction,” the report said.

“As this vapor trail passed behind a cloud, there occurred an explosion, which described by witnesses as intensely luminous, with a white nucleus surrounded by a reddish-orange periphery with radial lines of identically colored light. The explosion occurred in two pulses lasting between two and three seconds and from it two flaming objects of unequal brightness and size apparently fell, at disparate speeds, into the sea.”

A bright target was observed on the ship’s radar during the last 10 seconds of the fall of the slower of the two objects, the report said. The ship changed its course and searched the area for 5½ hours with no results.

Over the next eight days, an armada of more than 50 planes and 7th Fleet assets searched 75,000 square miles of sea around the clock between Guam and the Philippines. Two Stars and Stripes reporters covered the search.

“I remember flying around in the aircraft for hours and hours and hours,” former Stripes reporter Paul Rogers recalled recently. Rogers said no theories emerged at the time as to what happened to the plane. “We were really just looking for it.”

It didn’t take long for conspiracy theories to swirl. On the front page of the March 18 Japan edition of Stars and Stripes, the owner of the planes alleged that sabotage or hijacking were possibilities. Another Flying Tiger plane carrying secret military cargo destined for the area had crashed in the Aleutians the same day as Flight 739, killing one member of the crew. However, that crash was later attributed to pilot error.

The search for Flight 739 was called off March 23. Not a single piece of the aircraft, the bodies or any emergency life rafts were ever found.

The report stated that anyone with intent in Hawaii, Wake Island or Guam could have accessed the flight lines and aircraft and that the plane was left unattended in a dimly lit area in Guam.

George Gewehr, historian for Flying Tiger Line Pilots Association, said many in his organization have long believed it was friendly fire that brought down the plane. Hoge said her mother believed the plane was hijacked. Swander believes it was mechanical failure.

“The government has kept a tight lid on what did happen,” Gewehr said. “We didn’t pursue any investigation on it. It’s a pretty open-ended story on our part; we treated it as a bad accident and went on our way. I know if the truth could be found it would be a great thing for the families of all concerned.”

‘Thank God I didn’t get on that plane’

Dan Asensio and Johnny Byrnes — privates first class in communications — remember sitting at the Travis Army terminal with the 93 men. They also had received orders to Vietnam.

Asensio said the two men didn’t really fit in with the others — Ranger communications specialists trained in jungle warfare. He said the group appeared to be of a higher grade than he and Byrnes.

As the names were called out, each man stepped forward. Asensio and Byrnes were told there were issues with their passports and they were being held back. Neither man remembers seeing the South Vietnamese military men at the terminal.

Byrnes recalls going up to the bus that would bring the men to the doomed plane to say goodbye to a softball buddy he met at a command in Georgia. He doesn’t remember his name.

“I said goodbye and told him to save a few (enemy fighters) for me,” said Byrnes, who became a New York City police officer. “I’ll never forget those words … I’ll never forget them reading their names off and the guys stepping out.”

The pair would take a commercial flight later in the day. They arrived safely in Vietnam for their 13-month tour at a communications compound near Saigon, where they were told of the crash. Their families had believed they were dead for several days.

“I felt invincible after that,” Byrnes said. “Thank God I didn’t get on that plane.”

In the years since, Asensio has written letters to representatives to try and get the men’s names added to the wall.

“I get goose bumps thinking about how close I was to getting on that plane,” Asensio said. “My main concern is to get those guys’ names on the wall.”

The wall

The guidelines for inclusion on the Vietnam Memorial are mandated by Congress.

Since 1982, changes have been made to the eligibility requirements but the general rules state that the someone can be added if they died — regardless of cause or circumstance — within the designated combat zone boundaries, if combat-related wounds, accident or illness incurred in country led to their death elsewhere, or if they were “going to or returning from” a combat mission.

Army officials told Stars and Stripes that the men on Flight 739 did not meet the criteria for serving in the “Vietnam area of responsibility.”

Swander said he had hoped to prove that the men fell under the third option. However, with no documentation available, it has been impossible.

“The problem from day one has been to document that these men were on a ‘mission’ — as opposed to replacements or manpower escalation,” he said. “Unfortunately, all records showing what they were trained in, why they were picked and what they were going to do there have been redacted from their files.”

Swander said the men do not fit cleanly within the rules, which are open to interpretations depending on who looks at each case.

Over the years, there have been two exceptions, but both took special intervention.

Names have been added for a heart attack at a desk in Thailand, or a stateside suicide after being freed from a communist prison, Swander said.

But the example that most strongly supports including those on Flight 739 is the addition of names of servicemembers who died after a Marine Corps KC-130F crashed into the sea upon take-off from Hong Kong on Aug. 24, 1965.

The plane was returning to Vietnam from a rest-and-recuperation period so the troops on board could finish their tours, Swander said. The 54 Marines who lost their lives were added to the wall in 1983, and the five sailors who died were added a year later thanks to approval by President Ronald Reagan.

“Although the aircraft was en route to Vietnam, it was outside of the designated war zone,” Swander said.

Family anguish

Answers as to what happened to the men of Flight 739 and their mission remains elusive.

The only document received after requests from Stars and Stripes from any government agency was a report that detailed sorties that searched for Flight 739.

Despite the coordinates of the explosion being known, Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command officials never searched for wreckage because the incident was never assigned to them as a killed-in-action case, a spokesman said. A spokeswoman from the Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office said they are responsible for wartime losses only.

Neither the Air Force casualty office nor the Army’s Human Resources Command, which tracks casualties, had any information.

“It’s like they were meant to disappear,” Gloria Oliver Warmuth said. “They have been forgotten.”

Everyone briefed on the details of the case seems to be in agreement, that more needs to be done for the 93 that were lost.

“It really burns me up when things like this happen with the loss of an aircraft and its crew/passengers and the incident is quickly forgotten,” Travis Air Force Base historian Mark Wilderman wrote in an email to Stars and Stripes after finding nothing in an exhaustive search of their records. Failure to recognize their efforts dishonors the folks who lost their lives in the line of duty, he said.

Officials from Veterans of Foreign Wars agreed.

“Though we may never know why the aircraft went down, it would still bring great solace to surviving family members for their loved ones to be recognized for the mission they never got to complete,” said national VFW spokesman Joe Davis. “There are far worse things than dying for one’s country, and being forgotten tops that list.”

So time continues to pass; wives and siblings of the 93 passengers grow old or die. Their children have no place among fellow veterans to honor the fathers they barely knew.

“Getting their names on the wall in Washington, D.C., would be an awesome thing,” Howard Gallipeau III said. He believes his father deserves a spot. “He went to war and didn’t come home. He died for his country. That makes him a hero.”