This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

Play tells the story of Operation Babylift in Vietnam of 1975

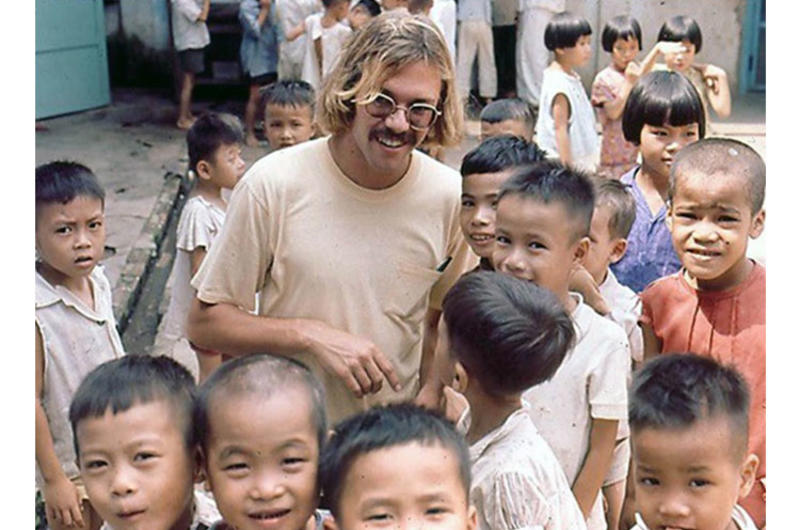

Ross Meador was part of Operation Babylift in Vietnam in 1975.

By Seth Robson | Stars and Stripes August 21, 2019

The voices of nine people involved in one of history’s most dramatic humanitarian operations echo in a play that aims to keep memories of the Vietnam War alive.

“Children of the April Rain,” by former National Archives employee Bill Doty, 77, will get a stage reading March 27 at a Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans event in Florida, according to Lana Noone, one of the people whose story is incorporated in the work.

The play tells the story of Operation Babylift, in which infants and small children were flown from Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, to new homes in America and other developed countries as communist forces closed in on the South Vietnamese capital after the withdrawal of U.S. forces.

Tragedy marred the start of the operation with the April 4, 1975, crash of an Air Force C-5A Galaxy transport near Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Vietnam, that killed 138. Military and civilian aircraft eventually flew more than 3,000 youngsters to new families overseas.

Doty, who worked in Hollywood before his time at the archives, got the idea for the play after talking to Noone about preserving the history of the operation in the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, he said in a telephone interview Tuesday from his home in Kansas City, Kan.

“This all happened during the fall of Saigon,” Doty said of his play, which he put together after talking to Americans involved in Operation Babylift.

“I said, ‘Let’s put all these things in chronological order and see if there is a story there,’” he said of his six-year effort to write the drama.

So far, the play has had several stage readings at veterans’ memorials, museums and churches but the goal is to turn it into a full production, said Noone, 72, of New York.

She and her late husband, Byron, had planned to adopt one of the Babylift girls and feared their daughter was on the crashed aircraft, she recalled.

“We were told our daughter was on the plane and everyone had perished,” Noone said in a telephone interview. “It took 24 hours to find out she wasn’t on the flight. She left Vietnam the following day and arrived in New York on April 23, 1975.”

However, the little girl, whose Vietnamese name was Mai Ngoc Tran and who the Noones called Heather Constance, was gravely ill and died May 17, 1975, of pneumonia.

“I promised Heather after the doctors told me there was no hope that I would spend my life making sure nobody forgets about Babylift,” she said.

The couple ended up adopting one of the last children evacuated during Operation Babylift, a baby girl they named Jennifer, now 44, she said.

Another whose story is featured in the play is Ross Meador, 65, of Fullerton, Calif., who went to Vietnam as a 19-year-old shortly after graduating high school.

Meador worked for an aid group, set up an orphanage in the South Vietnamese capital and helped send children to adopted parents in the U.S.

“In 1975 it became clear that the communists were coming and all these kids who were in our care… we couldn’t just leave them there so that’s how Operation Babylift was born,” he said in a telephone interview.

Meador drove the first group of evacuated orphans to a civilian plane that took them out of the country, spurring President Ford to authorize Operation Babylift, he said.

When the C-5 crashed, Meador, who was at the airport putting children on another plane, saw smoke rising and helicopters rushing to the downed aircraft, he recalled.

“After we got all the kids out, I stayed behind to donate medical equipment from our house to local hospitals and left on a helicopter from the U.S. Embassy roof on April 30,” he said.

Noone said she’d like to see the play made into a film titled, “110 Degrees in Saigon and Getting Hotter,” which was a code phrase sent across Saigon’s public address system warning Americans that they had two hours to get to the embassy before the Marines flew out, she said.

“When the helicopter left, they played the song ‘White Christmas’ signaling the end of America’s involvement in Vietnam,” Noone said

Meador said he also hopes somebody makes a film about Operation Babylift.

“My feeling is that it was one of the most important humanitarian efforts of the 20th century,” he said.