This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

Chinese-American Marines risked more than most on Korean War battlefields

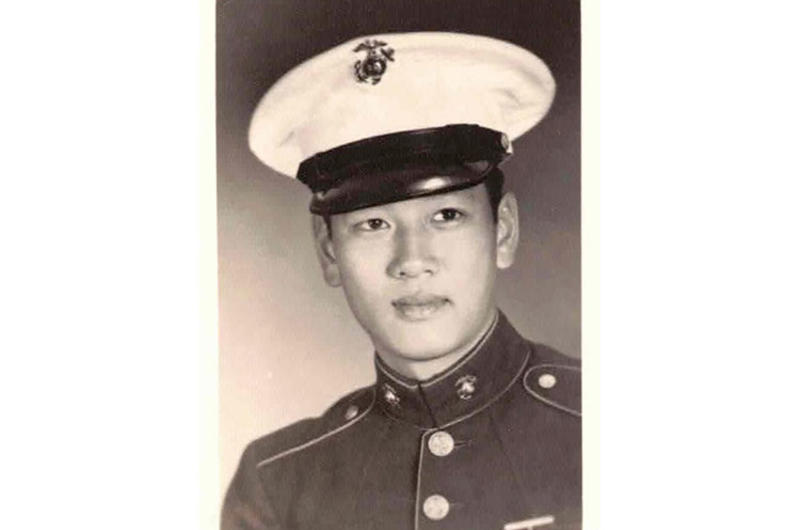

Franklin Chang at Camp Pendleton, before going to Korea.

By Seth Robson | Stars and Stripes June 21, 2020

More stories on the 70th anniversary of the start of the Korean War.

The possibility of dying from friendly fire was a worry for Franklin Chang, one of a small group of Chinese American Marines who fought in the Korean War.

The rifleman feared U.S. forces might mistake him for one of the communists, he said in a June 8 telephone interview from his home in Honolulu.

Chang, 87, recalled patrolling ahead of other troops and warning them to shoot off to the side if they saw him drop.

“At that time the enemy were stripping uniforms off our dead and wearing them because they were very poorly equipped,” he said.

The possibility of being a target for other American troops “when they see me with a Chinese face wearing a Marine uniform,” was a concern, Chang said.

Back in the rear, the Chinese Marines were sometimes mistaken for members of the Korean Service Corps — South Korean civilians who carried food and ammunition to troops in the field and often wore U.S. uniforms.

“They used to try to kick me out of the chow line,” Chang recalled, adding that people were surprised when he answered back in English.

Perhaps the most famous Chinese-American Marine to serve in the conflict is the late Maj. Kurt Chew-Een Lee.

The enlisted Marine in World War II became the Marines’ first Asian-American officer after earning his commission in 1946, according to his 2014 obituary in the Los Angeles Times after he died at 88.

“I wanted to dispel the notion about the Chinese being meek, bland and obsequious,” he told the newspaper in 2010.

Lee was an infantry platoon leader during the battle at the Chosin Reservoir in December 1950. He was wounded more than once and was awarded the Navy Cross for “extraordinary heroism” and Silver Star.

“To me, it didn’t matter whether those were Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, whatever — they were the enemy,” Lee said of the communists.

Chang, the son of a Chinese immigrant and a San Francisco-born Chinese mother, enlisted in 1950.

I was young and foolish,” he said. “I had seen too many movies.”

As a youngster he’d spent some time in China after his father moved the family back during the Depression. They returned to the United States after war broke out between Japan and China, he said.

In Korea, he was sent to the 1st Marine Division as a replacement and found himself standing at attention in front of a commander who didn’t want to send him or another Chinese American Marine to the front line.

“I said, ‘No sir, we are going to go up and join our companies,’” he recalled.

Six Chinese Americans served with the 1st Marines during the Korean War, Chang said.

“I knew all of them,” he said. “One was from New York, another was from Pennsylvania and the rest of us were from the San Francisco Bay area. They’ve all passed on now and I’m the last one standing.”

Seven decades after hostilities began — Friday marks the 70th anniversary of the Korean War — Chang recalls fighting in the mountains and manning observation posts near the front line that were hit by enemy fire each night.

His Chinese heritage wasn’t that helpful in dealing with the communists, he said.

“I didn’t speak any Chinese because I was raised American and went to an all-American school,” he said.

His final post in Korea was overlooking the village of Panmunjom, where an armistice agreement was reached July 27, 1953.

“I used to watch trucks come down from North Korea and trucks come up from the south for meetings in Quonset huts,” he recalled. “They just sat at the tables and looked at each other for 15 to 20 minutes and left. They never really talked. The United Nations had won the war already.”