This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

Guam seeks closure to its nearly 30-year quest for wartime reparations

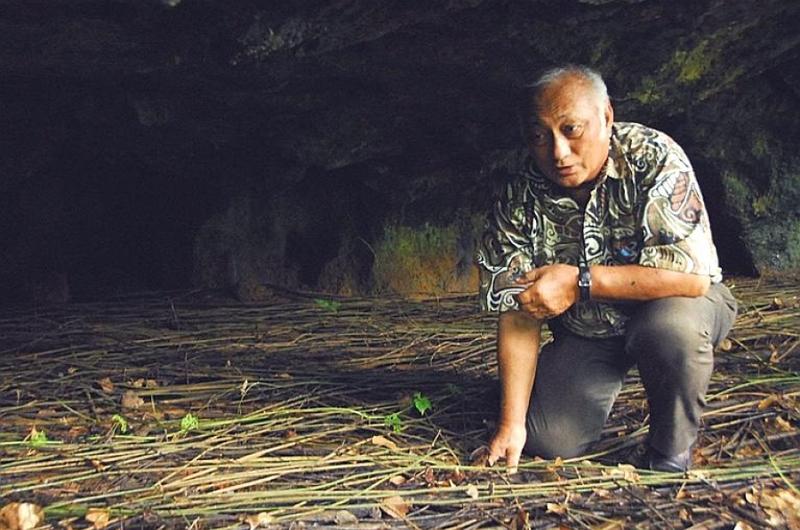

Chris Reyes, a World War II survivor, crouches in one of the caves where islanders, including his family, hid during the Japanese occupation of Guam.

By Travis J. Tritten | Stars and Stripes November 29, 2010

HAGATNA, Guam — Rita Santos Cruz is still haunted by the terrifying day when Japanese soldiers burst into her grade school and abruptly ordered all the students to line up outside.

Then the soldiers dragged Cruz’s pregnant mother into the school courtyard.

“They were beating her up,” recalled Cruz, who is now 73. “And here we were, watching her.”

Her mother, who had refused to bow to the Japanese forces occupying Guam during World War II, was beaten so badly she suffered a miscarriage, Cruz said, wiping away tears.

“We were not even Americans,” she said, “and we were punished.”

More than 60 years later, survivors of the Japanese occupation of Guam still harbor painful resentment — toward the United States. That’s because many feel the U.S. abandoned Guam at the outbreak of the war, letting it fall to the Japanese and thus condemning the population to mass executions, forced labor, torture, internment and rape at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Now, as the U.S. military pushes forward with its largest buildup here since World War II, the tiny U.S. island territory is pressing for closure of its wartime suffering and an end to its nearly 30-year quest for compensation from the federal government.

“If you want us to accept what is going on [with the buildup], let’s resolve this,” Guam Sen. Frank Blas said.

The Guam legislature declared in September that war reparations should be paid to survivors like Cruz as a condition of the planned $10 billion U.S. military expansion on the island, which will bring 8,600 Marines from Okinawa, visiting aircraft carriers and possibly a missile defense facility by 2014.

Meanwhile, Guam’s congressional delegate, Madeleine Bordallo, has said war reparations are her top priority in Congress and are “important for the military buildup to be successful.”

The total cost of reparations for the island could be as much as $126 million, according to a 2004 report by the Guam War Claims Review Commission.

The territory has been unable to strike an agreement with Congress on the payments — part of a legislative struggle dating back to 1983 — and the Guam legislature’s resolution in September is unlikely to exert any real leverage over the military buildup, which is set to begin within months.

The Joint Guam Program Office, which coordinates the buildup for the military, declined to comment on the war claims and referred all questions to the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

But the island is still pushing ahead doggedly on the reparations.

“It is just about the recognition,” said Blas, who founded the website www.guamwarsurvivorstory.com, dedicated to survivors and reparations. “Many were beaten, many were tortured. A lot of it was because of their loyalty to the United States.”

Chris Reyes, 69, who retired after two decades in the U.S. Army, is one of fewer than 1,000 Guamanians who endured the Japanese occupation on Guam and are still alive to tell their stories.

Reyes, who was just 4 months old when Japan invaded, said he remembers living in a dark jungle cave “like a mushroom” during the nearly three-year occupation because his family feared he would be killed.

His father was a slave laborer for the Japanese and fed a starvation diet while he unloaded cargo ships. Reyes said he eventually escaped into the jungle during a mass execution.

The only U.S. compensation his family ever received was $810 paid to his grandmother for land taken by the military immediately after World War II.

“Why did we suffer so much?” asked Reyes, who is now an outreach counselor for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs on Guam. “The American government did not provide protection [against a Japanese invasion], and Japan treated us like Americans.”

The United States determined before the war that Guam, then a U.S. possession and military outpost, would fall quickly to Japan, according to a history published by Andersen Air Base.

While Guamanians waited helplessly, all military dependents and U.S. citizens were evacuated from the island ahead of the expected Japanese invasion, which in December 1941 easily punched through a “meager, outdated” U.S. arsenal and about 600 inexperienced servicemembers, the air base history shows.

About 14,700 Guamanians were killed or endured hardship before the U.S. liberated the island from the Japanese in 1944, according to the National Park Service’s War in the Pacific memorial.

“Sisters looked at their brothers being killed with open eyes,” Reyes said. “Kids looked at their fathers being beheaded.”

Guam has always been patriotic — its 170,000 residents produce more military recruits per capita than almost anywhere else in the country — but there is also a strong underlying feeling that the territory was once snubbed by the U.S. government.

“People have very long memories,” said Ron McNinch, a political analyst and professor at the University of Guam. “War reparations are treated as a form of social transgression by these older people who felt they were wronged and their children, or now even their grandchildren, feel they were wronged or mistreated.”

Despite those feelings, the island’s claims of neglect are not so clear.

Guam received at least $8 million in compensation from the U.S. right after World War II, the Guam War Claims Review Commission showed in its 2004 report to Congress.

The claims commission was created by the Department of Interior to investigate the reparations issue and included the chairman of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, which handles U.S. war claims.

It found only about 716 Guamanians were compensated for death or injury from the war, though incomplete records don’t reflect a precise dollar amount for the claims compensation.

The lion’s share of Guam’s reparations went to 6,018 Guamanians who filed claims for lost or damaged property in the late 1940s.

Meanwhile, many Guamanians were not aware of the claims process and were not given enough time to file, according to the report.

Guam Sen. B.J. Cruz, a member of the claims commission and former chief justice of the Guam Supreme Court, said the U.S. has not settled its debt to Guam, despite the early reparations and arguments the U.S. lost 1,438 servicemembers in the liberation.

“There are some who will say the … Marines who died coming on shore are payment,” Cruz said. “We keep saying, ‘You are the ones who put us in the middle of this fire and you’re going to tell us because the firemen died trying to save us that we owe you?’ ”

The war claims commission recommended Congress pay an additional $126 million in reparations — $25,000 for each death and $12,000 for instances of rape, malnutrition, slave labor, forced march, internment or hiding to avoid capture.

The recommendation was sent to lawmakers in 2004 but was killed on the Senate floor by Sen. Jim DeMint, R-S.C., and a “small group of fiscal conservatives,” according to Guam Congresswoman Madeleine Bordallo.

Now, the payments are again being sponsored by Bordallo in the U.S. defense budget for the coming year — the same budget that contains initial construction funding for the $10 billion military buildup on Guam.

But Bordallo says there is still opposition in the Senate, especially the Armed Services Committee, which holds sway over defense spending and is headed by Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz.

Levin and McCain oppose paying the heirs of Guam war survivors and are concerned the payments could lead to more war claims in future versions of the defense budget, Bordallo said in a prepared statement on her website. She refused an interview with Stars and Stripes.

The senators offered Bordallo a compromise in 2009 — they would support the measure “if I agreed to limit claims only to those killed during the war and to those living survivors of the occupation,” she said.

But the compromise failed and the Armed Services Committee cut the reparations from the defense bill.

McCain refused to comment for this story. Levin did not respond to a request for comment.

This year, the Senate did not include the provision in its original version of the bill. The House bill contains the reparations along with a number of other controversial measures, including a repeal of the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” law, and may not pass at all this session.

Guam has been down this congressional path before.

Year after year, Guam congressional delegates, who have no vote, have made reparations a top issue and pressed lawmakers to approve payments.

Year after year, they have failed.

In 1988, Congress approved $12,000 payments to Aleutian islanders who were forced to relocate ahead of the Japanese invasion and occupation of Alaska, which was a U.S. territory at the time of the war.

Guam was nearly included in the reparations but the island legislature backed out of the deal in Congress, saying payments of $5,000 for personal injury and $3,000 for slave labor, forced march or internment were too small.

Few on the island are willing to compromise for less.

“With all this money they are giving away, the money we are asking for war reparations, hell, that is only a drop in the bucket,” said Vincente Taisipic, 74, a war survivor who retired from the U.S. Navy.

Chris Reyes is still waiting to finally get compensation and a formal apology from the U.S. government for the terrified times he and his family spent in a cave nearly seven decades ago.

“Money is not really the issue here,” Reyes said. “We are just confused as to why for so long we have been neglected.”