This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

My Lai: Where are they now?

By Nancy Montgomery | Stars and Stripes

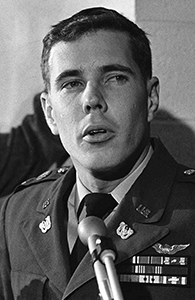

Lt. William Calley

Calley led one of Charlie Company’s three platoons and was responsible for numerous killings himself, was the only soldier convicted of a crime at My Lai. He was sentenced to life in prison but served only three days because President Richard Nixon ordered his sentence reduced. After spending three years under house arrest, he married and worked at his father-in-law’s Georgia jewelry store. Calley, 74, now lives in Atlanta.

Calley led one of Charlie Company’s three platoons and was responsible for numerous killings himself, was the only soldier convicted of a crime at My Lai. He was sentenced to life in prison but served only three days because President Richard Nixon ordered his sentence reduced. After spending three years under house arrest, he married and worked at his father-in-law’s Georgia jewelry store. Calley, 74, now lives in Atlanta.

In 2009, he offered a brief apology in a talk at a Kiwanis Club meeting in Columbus, Ga.

“There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai,” he said. “I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.”

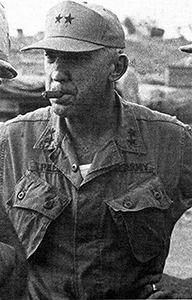

Col. Oran Henderson

The My Lai massacre occurred on Henderson’s first day as brigade commander following a career that had sent him to three wars and earned him four Purple Hearts, five Bronze Medals and five Silver Stars.

The My Lai massacre occurred on Henderson’s first day as brigade commander following a career that had sent him to three wars and earned him four Purple Hearts, five Bronze Medals and five Silver Stars.

After a cursory investigation into My Lai, Henderson reported that 20 Vietnamese civilians were inadvertently killed in artillery attacks or cross-fire. Henderson was court-martialed on charges of dereliction of duty, the highest-ranking officer to be tried. He was acquitted in 1971.

He retired as a colonel in 1974 and three years later became Pennsylvania’s director of civil defense. The 77-year-old died in 1978 of pancreatic cancer.

Lt. Gen. William Peers

Peers and his assistants, including two civilian lawyers from New York, interviewed, challenged and re-interviewed about 400 witnesses, including 50 in Vietnam, to come up with a damning report implicating dozens of soldiers and all levels of leadership in the My Lai massacre and cover-up.

Peers and his assistants, including two civilian lawyers from New York, interviewed, challenged and re-interviewed about 400 witnesses, including 50 in Vietnam, to come up with a damning report implicating dozens of soldiers and all levels of leadership in the My Lai massacre and cover-up.

Peers was a decorated veteran of World War II, a founder of the Green Berets and special forces who conducted counterintelligence and covert operations during the Korean War, and a former Vietnam corps commander. He was chosen to head the investigation because he was not a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy.

Peers was aware that the task would likely be thankless, that he’d be vilified as furthering the cover-up or making the Army look bad.

“You do this for me, and I’ll make sure you get that fourth star,” Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland told him, according to Peers’ daughter, Chris Neely.

Instead, Peers next assignment was as a deputy commander in Korea — serving under a four-star the Army brought out of retirement.

“He made the Army look bad. He got punished and the guys that murdered people didn’t,” Neely said. “He was appalled by that.”

Peers died of a heart attack in 1984 at age 69.

Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson

A 25-year-old Army warrant officer and helicopter pilot from Georgia, Thompson risked everything, including his life, to stop fellow soldiers from slaughtering Vietnamese civilians.

A 25-year-old Army warrant officer and helicopter pilot from Georgia, Thompson risked everything, including his life, to stop fellow soldiers from slaughtering Vietnamese civilians.

Thompson, flying over My Lai with his two-man crew in an observation helicopter, repeatedly landed to confront superior officers and other soldiers engaged in the massacre. He repeatedly reported it over the radio and again in person when he returned to base camp. What was supposed to be a several-day mission and could have resulted in thousands more deaths, was called off.

For years his heroic acts brought him disdain and hostility. It “broke Hugh’s heart,” his gunner, Lawrence Colburn recalled. But it didn’t break his will.

Over the course of two years of hearings on My Lai, Thompson told the truth “despite peer pressure, ostracism, threats of prosecution and a nationally televised congressional browbeating,” according to the Army’s chief prosecutor.

Thompson continued to fly observation missions in Vietnam, despite suspicions he’d been assigned missions purposely to get him killed. He was hit by enemy fire a total of eight times and in a final crash after his helicopter was brought down by enemy machine-gun fire, he broke his back.

In 1998, the Army did an about-face. Thompson and his crew were awarded the Soldier’s Medal in a ceremony near the Vietnam Memorial.

Thompson died of cancer at 62 in 2006.

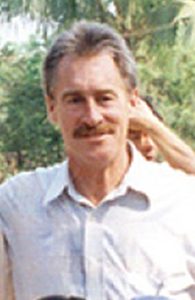

Spc. 4 Lawrence Colburn

Colburn was an 18-year old helicopter gunner who helped rescue a dozen people from My Lai, engaging in a tense standoff with fellow soldiers about to massacre a group of civilians hiding in a bunker.

Colburn was an 18-year old helicopter gunner who helped rescue a dozen people from My Lai, engaging in a tense standoff with fellow soldiers about to massacre a group of civilians hiding in a bunker.

As pilot Hugh Thompson coaxed the civilians out, keeping them behind him and radioing for their air evacuation, Spc. 4 Colburn and crew chief Glenn Andreotta trained their guns on the rogue troops, ready to fire on them if they fired on Thompson or the civilians.

Colburn said he was never certain whether he would have fired.

“That’s always the $64,000 question,” he said in a 2016 interview. “If I knew then what I know now … something like 125 children under 5 were killed. If I’d seen that, yeah, I would have opened fire.”

Colburn testified in post-My Lai hearings and courts-martial, knowing, he said, that it was mere “window-dressing.” He went back to Georgia after leaving the Army and opened a small business.

But My Lai haunted him.

“It took a huge chunk out of our lives,” Colburn. “We felt terrible we didn’t intervene sooner, that we couldn’t do more. We completely took the word ‘hero’ out of our vocabularies.”

After the Army belatedly recognized of the actions taken by Thompson, Andreotta and Colburn in 1998 with the Soldier’s Medal, Colburn made speaking engagements with Thompson, visited Vietnam with him, and, after his death, and set up a foundation in his name.

But nothing could erase so much misery.

“In My Lai, gallons of tears were shed,” he said. “I’ve been telling it for 47 years now. It’s hard to do it alone. And I can’t tell you how much I miss Mr. Thompson.”

Colburn died of cancer in 2016 at his home near Atlanta. He was 67.

Ronald Haeberle

Haeberle was a staff sergeant and Army photographer following Charlie Company’s 3rd platoon into the tiny hamlet in Son My.

Haeberle’s photos were undeniable evidence that a war crime had taken place.

He first published the photos in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, then sold them to Life magazine. Haeberle claimed that he did not turn in his film to the brigade because he believed it would be destroyed.

Haeberle, 76, lives in Ohio. Until he retired, he worked as a supervisor at manufacturing plants. In a September interview with the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Haeberle said he’d felt powerless to stop the killing or report them.

“I was kind of numb. I couldn’t understand why the small children, the women,” he said. “We all knew it was wrong,” he said. “You can’t just blame Calley. It’s everyone. It’s all of us.”

Lt. Col. Frank Barker

According to an Army inquiry, Barker, commander of Task Force Barker, gave the order to “burn the houses, kill the livestock, destroy foodstuffs and perhaps to close the wells” at My Lai, but gave no instructions to safeguard civilians.

Barker, like several officers in the division, monitored the operation from the air and filed a report claiming the mission left 128 enemy fighters dead but no civilians killed. Barker died in a helicopter crash three months later.

Capt. Ernest Medina

Medina, the Charlie Company commander who grew up poor in New Mexico, had a reputation as an aggressive officer who urged his soldiers to seek revenge for their dead comrades.

Medina, the Charlie Company commander who grew up poor in New Mexico, had a reputation as an aggressive officer who urged his soldiers to seek revenge for their dead comrades.

He was acquitted at court-martial in 1971 after the jury deliberated for an hour. He left the Army and worked for one of his lawyers, F. Lee Bailey. Medina died in 2018 at the age of 81.

Maj. Gen. Samuel Koster

Koster, the commanding general of the Americal Division, was serving as superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy when he was charged by the Army with trying to cover up the massacre.

The Army dismissed the charges but censured him, stripped him of his Distinguished Service Medal and demoted him to brigadier general.

Koster retired in 1973 and spent more than a decade trying to get the censure reversed.

In 1982, he told the Washington Post that “getting into Vietnam in the first place was where we made a mistake.”

He died in 2006 of cancer at age 86 at his home in Annapolis, Md.

Spc. 4 Glenn Andreotta

Andreotta, 20, was on his second tour of duty in Vietnam while serving as the crew chief aboard Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson’s helicopter. Andreotta was killed in action three weeks later when his helicopter was hit with small-arms fire.

He was posthumously awarded the Soldier’s Medal in 1998.

Ron Ridenhour

Ridenhour was a gunner in a different unit when shortly after the massacre he started hearing about it from friends. He interviewed a number of the participants, and after he returned to the U.S., he sent a registered letter to 30 officials exposing the massacre and asking for an investigation.

In one televised interview he said he’d decided that he couldn’t live with knowledge of the massacre and not try to see justice done.

Ridenhour went on to become a prizewinning journalist. He died of a heart attack at 52 in 1998. The Ridenhour Prizes, which recognize truth-telling to “protect the public interest, promote social justice or illuminate a more just vision of society,” are named for him.