This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

Vietnam at 50: For those who prepared Vietnam's fallen, a lasting dread

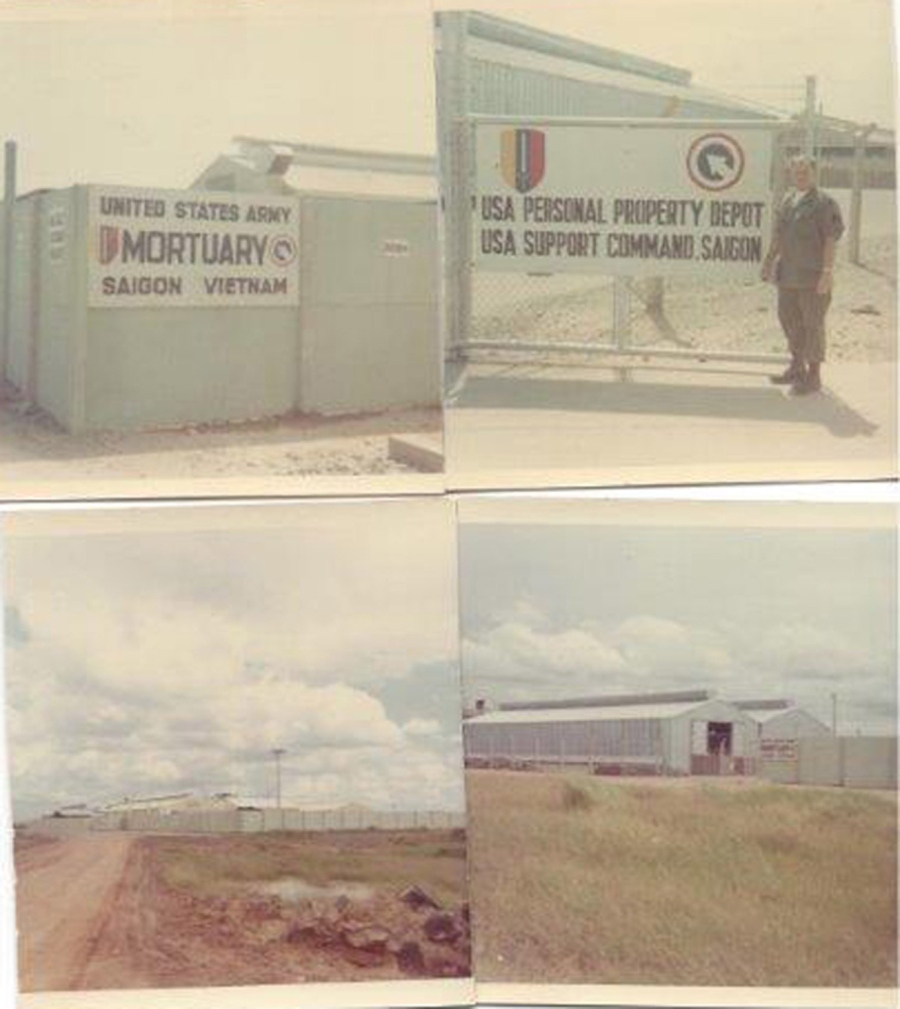

The remains of four U.S. servicemen killed in the Vietnam War prepare to make the final journey home from the U.S. Army mortuary at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon.

By Matthew M. Burke | Stars and Stripes November 4, 2014

The faces haunt him wherever he goes.

Day, night, asleep, awake; the dead are unrelenting. They are young, horrifically burned, maimed, bloated beyond recognition, others just in pieces.

Gary Redlinski says he can hear the Hueys, Chinooks and C-130s, all bearing dozens upon dozens of bodies in a never-ending procession. The putrid smell tickles his nose.

The Vietnam War left scars on the minds of a generation, but for the soldiers who identified the war dead and sent them home to their families for burial, it has never been more vivid.

“I hear a chopper today and it puts me on alert,” Redlinski told Stars and Stripes from a reunion of mortuary affairs and graves registration workers in September. “I’m like, ‘OK, I have more work to do.’ … Vietnam is still with me as clear today as it was back then.”

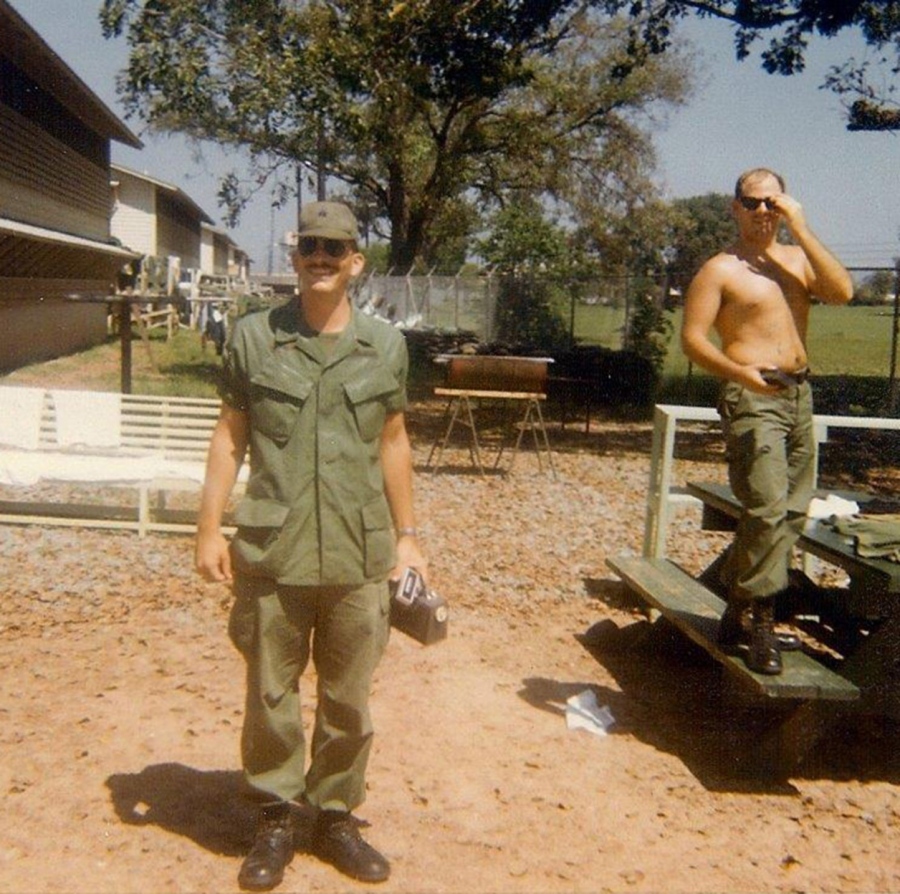

From May 1968 to July 1970, the Army sergeant came of age in the U.S. Army mortuary at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon. Just 19 when he arrived, the horrors he witnessed would forever shape him and the men he served with.

“It was really rough,” Redlinski said. “The numbers were overwhelming.”

More than 58,220 Americans would die before it was all over.

A grim task

Redlinski, a native of Buffalo, N.Y., couldn’t have picked a worse time to head to Vietnam. Casualties had skyrocketed from 216 in 1964 to 16,899 in 1968, according to U.S. government statistics. He was in school to become a funeral director when he was drafted. The move to the Quartermaster Corps and the Army mortuary was only natural.

Glen Fruendt had been in a similar situation. The 23-year-old had been in the family funeral business in Chicago when he was drafted. He arrived at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in September 1967.

The Army mortuary had been set up in a building previously occupied by the French, they recalled. It was originally located by the flight line and heliport for easy access to incoming remains.

The remains came in from mortuary personnel in the field who were overseeing smaller collection points spread out across the country. They were airlifted or sometimes driven into one of the two main mortuaries, one at Tan Son Nhut and the other at Da Nang.

The capacity of Tan Son Nhut was 250 sets of remains, Redlinski said. However, they always had more.

Fruendt remembers spending days bringing bodies in from the heliport, and days just getting them off the floor.

The mortuary was bustling around the clock, seven days a week.

They were so far over capacity that Fruendt recalls staff throwing food away to make more cooler space.

“There were remains all over the place,” he recalled. “It almost became a normal way of operation because we were so busy.”

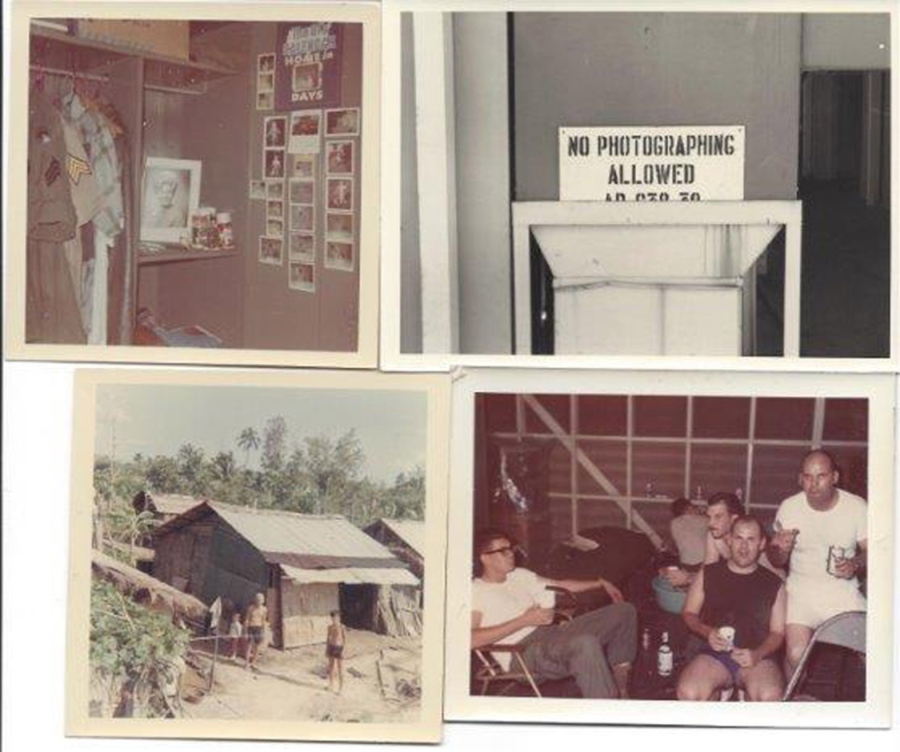

The first task mortuary personnel had after bringing the remains into the facility, was to take the clothing off the individual. They would then look for identifying marks like scars, birthmarks or tattoos.

They checked the boots and belts of the individual to see if their name had been written inside.

“Dog tags were the worst thing you could use for an identification,” Fruendt said. “Guys would trade them or give them to their buddies. Some guys would come in with three sets on them, none of them their own.”

Then the men would take fingerprints and make a dental chart. These were the best tools they had to make an ID. But it wasn’t always easy. Bodies would come into the mortuary in pieces sometimes, burnt, bloated from days in the hot sun of a rice paddy or covered in maggots.

“You learned to breathe a certain way,” Redlinski said. “The odors were difficult to deal with sometimes.”

Army personnel would often help embalm the bodies because the civilian embalming crews could not keep up with the work load.

The toughest IDs would be tasked to civilian anthropologists. Army mortuary staff would aid in the work. It was like a puzzle trying to put bone fragments together, Redlinski said.

“It got to be a lot more gruesome than I thought it would be,” he recalled.

Some cases went unsolved. If there was too little left of a group of men, they were sometimes shipped back together.

Mistakes were rare but they were made, the men said. One family was sent the wrong remains from the mortuary in Da Nang, Fruendt recalled. After they continued receiving letters from their loved one in the field, an inquiry was launched and standards improved.

The faces

As the decades have slowly crept by, mortuary personnel have tried to forget, but that is all but impossible.

Redlinski recalls a man whose skin was peeling off. To make the ID, he had no choice but to put it on his own hand to take a fingerprint.

“It still haunts me to this day but we got him home and back to his family,” he said. “That was the good part. I try to remember the good parts. We did what we had to do I guess.”

Fruendt still sees the face of a young female nurse who had come in after overdosing on drugs.

“She was beautiful on her ID card but now she was all bloated and just in terrible condition,” he recalled. “I was shocked that nobody had recognized the difference” and tried to help her.

There were high-ranking officers caught skimming money who committed suicide and deserters who hugged a grenade rather than be returned to the military.

The mortuary men got through it by trying to shut down their emotions. However, they still had to have respect for the grim task at hand.

“We treated the remains of the soldiers that were killed with respect,” Fruendt said. “It was sad but you had to do the job right and you had to treat them like a member of the family.”

For Redlinski, it was cathartic to talk to the dead.

“I would say, ‘Sorry I have to do this. I have to get you back to your family.’”

‘Very personal’

Leamon Smith went to mortuary school as well and enlisted rather than waiting to be drafted. He arrived in Saigon in February 1969 at the age of 22.

The California native was in “personal property,” so he was tasked with going through the personal effects of each servicemember who came through the mortuary. He would take out anything that might cast a negative light on the deceased or be hurtful to the family like naked pictures or letters with cursing or those from a mistress.

“We kind of censored some of that out,” he said. “I had to go through every piece of paper in a guy’s wallet. Anything derogatory, we’d have to take out.”

This meant reading all the letters from home and seeing photographs of babies that the deceased would never meet.

“You almost knew them,” he recalled. “Maybe you saw a picture of their mom and dad, or their girlfriend or sister, and you’re connected. It was very personal and very deep.”

Smith would also see their bodies in the mortuary.

One day, he saw a familiar face. It was his supervisor from a mortuary post in Germany, Sgt. Bill Dawson.

“He was killed in the field,” Smith said. “When you’re a young person, you don’t think you’re going to die. That’s why you can send young people to war. Nobody thinks they’re going to die. It was very difficult when he came through.”

'It permeates you'

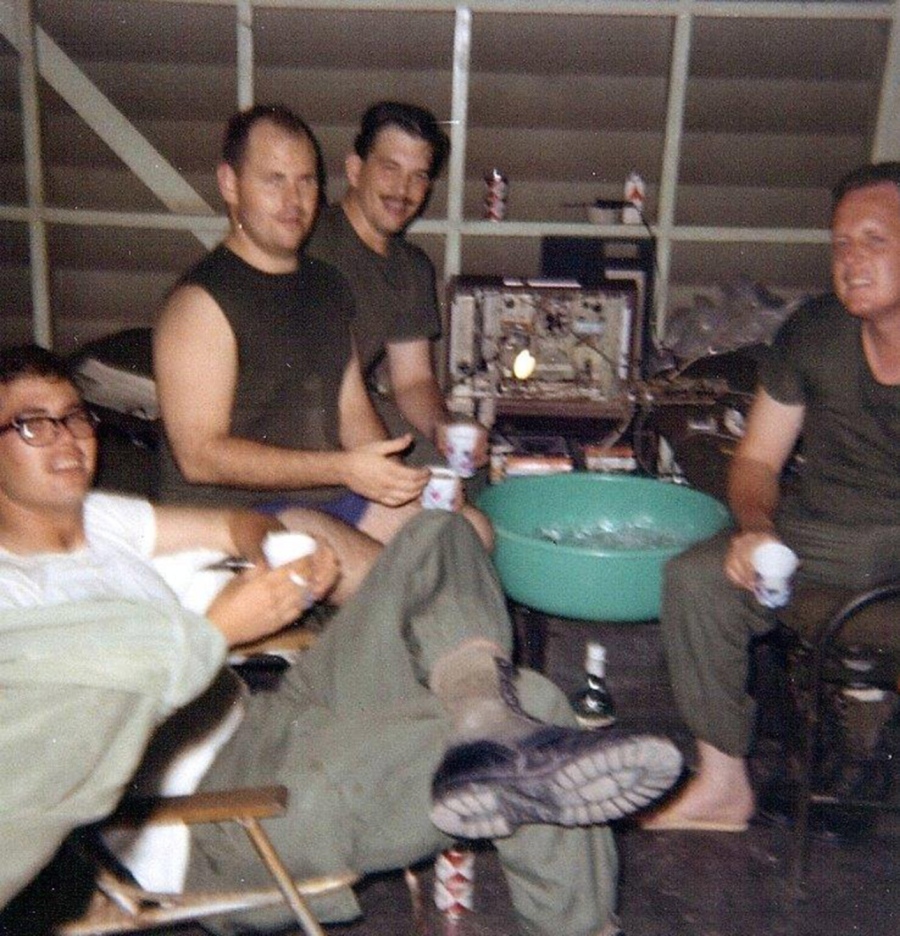

The Army mortuary personnel were outcasts, shunned by their peers because of their job.

“We stayed to ourselves,” Redlinski said. “People thought, ‘Oh there’s death, I don’t want to be near you.’”

Fruendt remembers heading to the chow hall with the members of his unit one day after work. They had all showered and were wearing fresh clothes. They sat down and started eating. Before long, they realized that everyone had cleared away from them.

“The smell was vicious,” he said.

“No matter how much you wash your hands or clothes, it permeates you,” Redlinski added. “It permeates your skin.”

Redlinski said that the smell even reached the troops outside the mortuary.

Just before Fruendt left Vietnam in the fall of 1968, a new, bigger, better mortuary had been built at Tan Son Nhut. This one was far away from the other troops.

“We were kept away from the main body of troops because it was demoralizing,” Redlinski said. “Most guys never knew we were there.”

The toll

The mortuary men said they would never forget the faces of the young men and women they had seen and the horrors of war. They would struggle with post-traumatic stress, leading to a host of problems that went well beyond nightmares — anger issues, substance abuse, failed marriages, being cast adrift.

Fruendt had to walk away from the family mortuary business, much to his father’s chagrin. Redlinski worked in the field for some time, but ultimately quit as well.

Redlinski didn’t realize the extent of his problems until the ‘90s, when he went to visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. As he looked at the sea of names carved in stone, he realized that in addition to his sorrow, he was angry at the dead for what they had put him through.

“I realized how those guys had affected my life,” he said. “It was tough.”

When things get tough, just like during wartime, the men lean on each other. They attend meetings and find solace in yearly reunions. They are now focused on supporting the current generation of Army mortuary personnel.

“It takes a toll on you,” Fruendt said. “You don’t realize the change in yourself until later on.”

A brotherhood

Since Vietnam, very little has changed in training and operations of the Army’s mortuary personnel, according to Bill Ellerman, an instructor at Joint Mortuary Affairs Center at Fort Lee, Va.

“Believe it or not, there has been very little innovation between the Vietnam-era and today,” Ellerman said. “We [now] have that airlift capability so we don’t embalm in theater anymore. We’re still fingerprinting and dental charting.”

Their ranks have ballooned from about 400 during Vietnam, who were spread out among small supply and service company teams and detachments, to about 1,600 soldiers in dedicated mortuary affairs companies.

The two active-duty companies are based out of Fort Lee. Six reserve companies are based out of Delaware, New York, California, two in Puerto Rico and one spread around the Pacific.

The Army’s mortuary personnel are still the experts in recovery, identification, preservation and safeguarding remains until a deceased servicemember can be sent back home to their family. It is one of the most important missions during war, Ellerman said.

“There is no better way to honor the fallen then to return them back to their home,” he said.

That is still the mission, one that is still largely unheralded.

“They didn’t get the credit they deserved,” Ellerman said of the Vietnam veterans who came before him. “It’s kind of the same way today.”

COURTESY OF U.S. ARMY QUARTERMASTER MUSEUM

COURTESY OF U.S. ARMY QUARTERMASTER MUSEUM

COURTESY OF U.S. ARMY QUARTERMASTER MUSEUM

PHOTO COURTESY OF GLEN FRUENDT

PHOTO COURTESY OF GLEN FRUENDT

PHOTO COURTESY OF LEAMON SMITH

PHOTO COURTESY OF LEAMON SMITH

PHOTO COURTESY OF LEAMON SMITH

PHOTO COURTESY OF LEAMON SMITH

COURTESY OF U.S. ARMY QUARTERMASTER MUSEUM

COURTESY OF U.S. ARMY QUARTERMASTER MUSEUM

COURTESY OF U.S. ARMY QUARTERMASTER MUSEUM

PHOTO COURTESY OF GARY REDLINSKI