This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

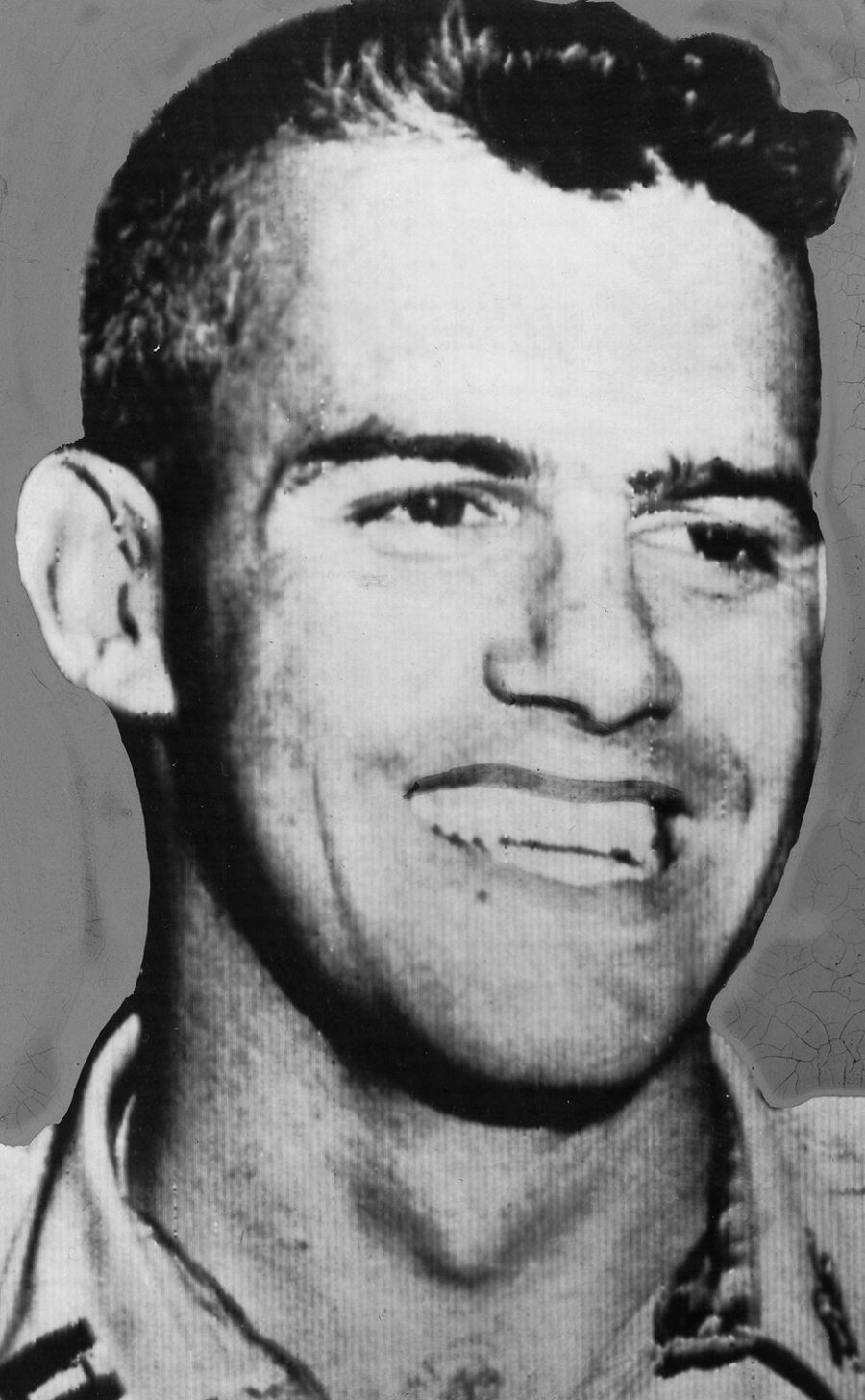

Vietnam at 50: Soldier who stood firm against Viet Cong captors inspired fellow POWs, earned Medal of Honor

At his home near Baltimore, Stephen Versace, younger brother of Medal of Honor recipient Humbert "Rocky" Versace, holds the medal his brother was posthumously awarded after a long campaign by supporters in 2002 for heroic resistance while in Viet Cong captivity.

By Chris Carroll | Stars and Stripes October 28, 2013

“VIET VICTORY NEAR,” blared a headline across the top of Stars and Stripes’ front page.

Farther down the page, a smaller article titled “3 Aides Seized in Vietnam Battle” told a far less celebratory tale. Three soldiers serving as advisers to Vietnamese government troops south of Saigon were feared to have been captured a few days earlier by the Viet Cong during a failed raid.

The date of the edition was Nov. 1, 1963.

For the men taken captive, years of torment lay ahead. At home, the nation would descend into increasing turmoil as U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War deepened.

Two of the soldiers snatched would return to the United States, but the body of the third, Capt. Humbert “Rocky” Versace, still lies in an unmarked grave somewhere in the Mekong River Delta. Versace’s heroic and ultimately fatal resistance to his Communist captors resulted in the posthumous awarding of the Medal of Honor to him in 2002.

It wasn’t the first Medal of Honor awarded to a Vietnam veteran; that honor went to Army Special Forces Capt. Roger Donlon, who in 1964 ignored serious wounds while leading the defense of a Special Forces camp from an enemy attack and rescuing several fellow soldiers.

But Versace’s medal covers the earliest time period of any Medal of Honor awarded for service in Vietnam, having been awarded for cumulative acts that began in late 1963 and continued until his death at age 28 on Sept 26, 1965.

As a fellow prisoner of war, Army Special Forces officer James “Nick” Rowe later explained to one of Rocky Versace’s younger brothers, “When you’re awarded the Medal of Honor, it’s for a moment of your life that may be over in a second, but it’s so outstanding and beyond that call of duty that it’s never forgotten,” said Stephen Versace. “What Nick Rowe said is that Rocky had those split-second moments of decision for two years, and he met every one of them.”

Capture

The fact that Versace had just six weeks left in his second tour in Vietnam as an Army intelligence adviser didn’t stop him from volunteering to accompany a dangerous mission on Oct. 29, 1963, aimed at destroying a Viet Cong command post deep in enemy-controlled territory.

According to Rowe, who later chronicled the mission and ensuing years of captivity in a book, “Five Years to Freedom,” intelligence advisers like Versace weren’t allowed to accompany such missions. But Versace, who friends and relatives say could not be dissuaded once he made up his mind, insisted on going.

“The probability of making contact with Charlie and provoking action, coupled with the chance of picking up good intelligence in the previously untouched village, were enough reason for Rocky,” wrote Rowe, who in 1963 was a Special Forces first lieutenant advising South Vietnamese troops.

It was the early years of the Vietnam War, before a vast influx of troops and weaponry that would eventually give the U.S. military the ability to project force around the country. For this mission, the three soldiers — Versace, Rowe and Special Forces medic Sgt. Daniel Pitzer — along with a company of South Vietnamese troops, would be going against the enemy without the promise of air cover, and with spotty artillery support.

The assault went badly, and within hours a Viet Cong battalion moved in. After a fierce defensive battle, Viet Cong troops captured Versace, who had been seriously wounded by several gunshots in his legs and back, along with Rowe and Pitzer.

Although the treatment they received was at first relatively mild, according to Rowe, it took only days for Viet Cong officials, determined to re-educate the men, to realize that Versace was a particularly hard case. He had immediately begun disputing their political claims. Soon, he was being held separately from the two Green Berets, Rowe wrote.

“It was becoming clear that the separation was not based on his wound or the “hospitalization” he had never received. Rocky had assailed the revolutionary movement from his first encounter … and had been marked as a definite reactionary.”

Resistance

Soon after the capture, Versace made his first escape attempt, breaking out of the hut in the U Minh Forest, a Viet Cong stronghold, in hopes of swimming through canals to freedom. Severely disabled by his leg wound, Versace didn’t make it far.

The shackles, physical punishment and isolation that resulted from the attempt, as well as other acts of rebellion, didn’t stop Versace from trying three times more to escape.

Versace was a man of unbending Catholic faith, and he had accepted the tenets of the Army with nearly as much ferocity, said his brother. One of those was the Code of the U.S. Fighting Force, which famously instructs captured troops to attempt escape and give nothing but “name, rank, service number and date of birth.” Other than giving constant argument as well, Versace followed the code to a T.

“If Rocky thought he was right, he was very difficult to deal with,” Stephen Versace said. “If he knew he was right, he was impossible to deal with. There was nothing you could do.”

Versace spoke French and Vietnamese, and the fact that, as Pitzer later stated, he told them they could “go to hell in three languages” caused his communist guards to lose face. It also angered superiors who wanted to indoctrinate the soldiers and use them as propaganda tools against U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

During a visit of high-ranking communist cadres, Rowe wrote that he heard Versace shouting, “I’m an officer in the United States Army. You can force me to come here, you can make me sit and listen, but I don’t believe a damn word of what you say!”

As he longed for freedom, Rowe wrote that his own determination to resist had been wavering, Versace’s “hard core” attitude gave him new strength.

The last time his fellow prisoners heard from him, in early April 1964, he was loudly singing “God Bless America” to his stymied captors. The following day, Rowe was shown a pile of bloody clothing and a ravaged cell.

He assumed Versace was dead.

Torment and death

The Viet Cong had other ideas for Versace. Perhaps to limit what they saw as his bad influence on other prisoners, he was moved to a succession of camps. The following year, Rowe was overjoyed to spot him from a distance, but was shocked at his appearance. Though he was still in his 20s, Versace’s hair had turned entirely white, and he was gaunt and jaundiced.

This was the Versace that Army Capt. Jack Nicholson, also an adviser to South Vietnamese troops, kept hearing about as he combed the Mekong Delta for signs of him.

He’d first encountered him at West Point, when Nicholson was a senior in charge of disciplining Versace, a freshman who’d sneaked out after hours.

“He didn’t make any excuses or try to explain; [he] just said, ‘Yes, I did it, I went out, I got caught, and that’s it,” said Nicholson, who retired from the Army as a brigadier general. “I kind of admired that attitude of not whining about anything.”

Nicholson led willing units of South Vietnamese troops on four missions to rescue the captives in 1963 and 1964. The groups took heavy casualties and seemed to come close several times.

“We’d find warm food, cooking fires, but no Rocky,” he said.

Nicholson also spoke to peasants and villagers, some of whom told him of witnessing Viet Cong troops taking a foreigner — starved and sickly but unbowed — from village to village.

“He was paraded around by torchlight, and their intent was to show these people the ‘aggressor,’ ” Nicholson said. “He would openly defy them in Vietnamese and French, and they would hit him in the face with rifle butts.”

In one village, an old woman told Nicholson that after one such assault, a bleeding Rocky Versace looked up to heaven with a smile, and echoing Jesus’ words in the Gospels, asked God to forgive his captors.

As he was dragged around the Delta, Versace was becoming a martyr in the literal, spiritual sense, Nicholson said. The intention to humiliate and degrade the American was backfiring as the Vietnamese who witnessed the spectacle began to respect the unbowed captive with an unshakable religious faith.

“I heard from the people I spoke to that he was converting his captors,” Nicholson said. “I think that’s why they decided they had to kill him.”

On Sept. 26, North Vietnamese radio announced Versace had been executed, a payment of “blood debts to the Vietnamese people.”

Downgraded

In a famous escape, Rowe clubbed his guard and slipped away from the Viet Cong on Dec. 31, 1968. (Pitzer had been released the previous year.) Soon after his return to the United States, he found himself in a meeting at the White House with President Richard Nixon.

His account of captivity deeply moved Nixon, and Rowe focused on Versace’s fearless conduct. It was his example that gave other prisoners strength, Rowe said, while Versace’s incorrigibility effectively took pressure off the others.

Nixon reportedly agreed with the contention that Versace deserved the Medal of Honor, and Rowe quickly wrote a nomination. The process soon became mired in bureaucracy — and, many believe, bias in the Army. Versace instead was awarded the Silver Star.

“I just don’t believe the Army at that time was willing to give the Medal of Honor to someone who was a prisoner of war,” Stephen Versace said.

Rowe left the Army in 1974, but returned to active duty several years later and was killed by a communist assassin in the Philippines in April 1989. The end of his storied career seemed to close the book on his dream of a posthumous Medal of Honor for Rocky Versace.

Award

The effect of Rowe’s 1971 book lived on, however. In 1997, an Ohio postal worker and Army veteran, Duane Frederic, read “Five Years to Freedom,” which spurred him to begin a research project on POWs held in secret jungle camps.

“I reviewed a lot of the jungle POW records on microfilm from the Library of Congress, and I went through reels and reels and reels,” Frederic said. “I had a feeling for the level of heroism many of these men exhibited, but were never recognized for.”

He also developed the conviction that Rocky Versace’s actions throughout his captivity were as fearless and self-sacrificing as those of any Medal of Honor recipient. Using Rowe’s book as well as his other research, Frederic began putting together a more systematic nomination for the award.

Soon after that, Frederic met an informal group in Washington calling itself the “Friends of Rocky Versace.” The members had known him during school, served with him in the Army or developed an admiration for him after his death. Now the group was attempting to get a new school in Alexandria, Va., where Rocky Versace lived while attending high school, named for their hero.

Using their Washington connections, the Friends of Rocky Versace — including some high-ranking military officers — advocated for the nomination with Congress and the Pentagon. Members of Versace’s class of 1959 at West Point joined the effort, and the new nomination picked up steam.

The school-naming effort failed, but Alexandria instead approved a memorial plaza for Versace at a local recreation center. The plaza was dedicated on July 7, 2002, and the following day, Rocky Versace was awarded the Medal of Honor by President George Bush in a White House ceremony.

“In his too short life, he traveled to a distant land to bring the hope of freedom to the people he never met,” Bush told the assembled crowed. “In his defiance and later his death, he set an example of extraordinary dedication that changed the lives of his fellow soldiers who saw it firsthand. His story echoes across the years, reminding us of liberty’s high price, and of the noble passion that caused one good man to pay that price in full.”

RICK VASQUEZ/STARS AND STRIPES

RICK VASQUEZ/STARS AND STRIPES