This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

Vietnam at 50: The first rock and roll war

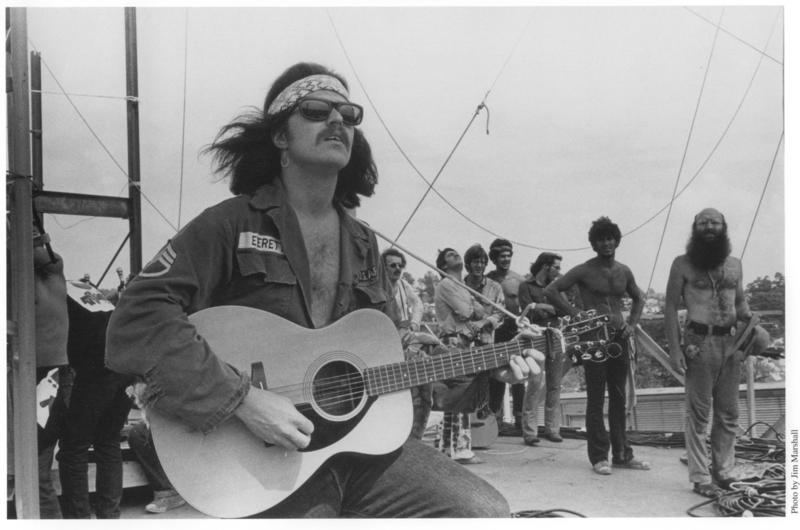

Country Joe McDonald at Woodstock in 1969. McDonald, a Navy veteran, performed his "Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag," which was one of the most memorable moments in the 1970 film documenting the festival. The song was popular with the anti-war movement, and the troops also appreciated its gallows humor.

By Sean Moores | Stars and Stripes

The sonic revolution and one-upmanship that defined 1966 make a compelling case to call it the greatest year in music history.

Just two years after the Beatles fired the shot across America’s bow that started the British Invasion, the mop tops had matured as songwriters and recording artists. In August 1966 they released “Revolver,” a fully realized work that helped the album supplant the single as rock’s dominant art form.

The other major players in the game of catch-me-if-you-can, The Beach Boys and Bob Dylan, released albums on the same day that are regularly ranked with “Revolver” on the best-of-all time lists — “Pet Sounds” and “Blonde on Blonde,” respectively. Add a slew of great soul and garage rock singles, and it’s hard to argue that another year was measurably better.

In the early months of ’66, though, a one-hit wonder had the pop charts moving to the beat of a different drum: the martial snare of Army Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler’s “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” which was the No. 1 song in America for five weeks. Sadler’s was far from the only musical moment of Vietnam, which came to be known as the Rock and Roll War.

The unofficial title is generally attributed to the late Michael Herr, whose 1977 book “Dispatches” detailed his time as a war correspondent in Vietnam for Esquire magazine. The book is an excellent example of New Journalism, the style that combined literary techniques with traditional reporting.

Herr writes with a novelist’s detail about “cassette rock and roll in one ear and door-gun fire in the other” in one memorable passage. Although Herr receives credit for the title, the particular phrase first appeared in a review of Herr’s book, by New York Times critic John Leonard: “It is as if Dante had gone to hell with a cassette recording of Jimi Hendrix and a pocketful of pills: our first rock-and-roll war, stoned murder.”

Music is all over Herr’s book, as it was all over the Vietnam era. It was a vibrant thread woven through the entire tapestry of the ’60s. It changed the way troops went to war. It gave them a way to bond in a far-off place they wanted to leave. It helped them process their experiences once they came home.

On the homefront, music mobilized the anti-war movement. It was a time of chaos in-country and more chaos on campus. For the first time, TV gave people a front-row seat to war on the nightly news. The news was not good. Khe Sanh. Body counts. Four dead in O-hi-o.

Activists and troops had songs in common, although they had slightly different meanings for each group. That soundtrack, although less homogenous than popular films and TV shows would have us believe, became ingrained in our cultural consciousness. It also sounded a loud call for change, its final notes still reverberating.

Technology makes it possible

Music has always been part of war.

In early American conflicts, songs were sung by troops to help keep spirits high, like “Yankee Doodle” and “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Vietnam was the first war in which technology made music widely accessible everywhere except the front lines.

It was different from previous wars, “certainly in the way that soldiers were able to personalize it,” said Hugo Keesing, who taught psychology in Vietnam for the University of Maryland in 1970 and ’71, primarily to military personnel at Phan Rang Air Base. “There was a great deal of personalization of musical tastes, because it was possible.”

In World War II and the Korean War, troops had to gather in central locations to hear radio broadcasts. In Vietnam, technological advances included portable transistor radios and tape decks. In addition to records bought at the post exchange and on the local economy — often for pennies on the dollar — GIs could buy high-end cassette recorders and reel-to-reel tape decks at reasonable prices to record the songs they wanted to hear. (It quite likely gave rise to mix-tape culture, in which future generations would woo the opposite sex by presenting carefully curated playlists.)

In “Armed With Abundance: Consumerism & Soldiering in the Vietnam War,” Meredith H. Lair writes that by 1969, more than one-third of American troops listened to the radio more than five hours a day. For GIs between 17 and 20, the number was 50 percent.

Armed Forces Vietnam Network radio wasn’t popular with everyone. Some younger troops complained that it catered to officers, at times keeping a tight fist on the playlist. It did, however, attempt to present varied programming.

“There really was music for everyone,” said Keesing, who curated a 13-CD-plus-book box set “Next Stop is Vietnam: The War on Record 1961-2008.”

“You got the Top 40 stuff coming in. You had Wolfman Jack that you could listen to on the radio. ... One of the favorite DJs who prepared her program back in L.A. but whose records came over was Chris Noel. So there were programs for every taste and there were a few places where all of those tastes, I think, coalesced, and it would be those songs that would be the soundtrack” of U.S. troops in Vietnam.

In 1969 and ’70, Lair writes, servicemembers bought nearly 500,000 radios, 178,000 reel-to-reel decks and 220,000 cassette recorders.

“When I was there, music became a primary morale booster. (The brass) wanted to give us the creature comforts. They wanted to keep our morale up,” said Doug Bradley, 69, who served as an Army information specialist at Long Binh in 1970 and ’71. “Music was one of the real mainstays. (They said), ‘We’re going to let these guys buy radios and they can buy tape decks and they can buy cassette decks and they can buy guitars.’ … The fact that we had that kind of access and ways to disperse the music that they didn’t have before, I think really makes (Vietnam) different.”

Vietnam vets’ national anthem

The early years of the war had a different soundtrack than the one we now commonly associate with Vietnam. The first troops in-country were generally older, military lifers. Some had fought in Korea. Some liked early rock and roll, but tastes for many trended to crooners, classical and country.

Country music, such as Johnnie Wright’s 1965 hit “Hello Vietnam,” tended to express the belief that, although there would be sacrifices, the United States would prevail in its just fight against the spread of Communism.

As music began to change, so did the American force in Vietnam. Troops, on average, got younger, and their tastes reflected that. The teenagers who watched the Beatles change the world on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1964 were now fighting in a foreign land. This was their war, with their soundtrack.

Songs didn’t have to be explicitly about Vietnam to carry special meaning for troops. Like the generations before them, these GIs missed home. Songs such as The Temptations’ “My Girl” (1964) and the Box Tops’ “The Letter” (1967) reminded them of what they’d left behind.

One song in particular galvanized GIs in their desire get back to the States: The Animals’ 1965 hit “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” The get-out-of-the-ghetto song, written by Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, was a good fit for The Animals, who hailed from industrial Newcastle upon Tyne, England. A Vietnam anthem wasn’t part of the plan for the writers or the artists.

In “We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War,” Doug Bradley and Craig Werner explain how and why U.S. servicemembers used music to understand the complexities of Vietnam in-country and back home. Through hundreds of interviews with those who were there, the authors heard time and again how their title track was a touchstone for the troops. They sang along with it on the radio. They listened to it in their hooches. They heard it in the enlisted men’s clubs, played by Filipino cover bands.

“It’s the Vietnam vets’ national anthem,” Bradley said. “We heard it time and time again. For me, in Vietnam, it’s literal because we had a DEROS date (Date Eligible For Return From Overseas) and everybody knew — Marines (were in Vietnam for) 13 months, Army 12. So you sang that song with a little more gusto every time that you got a little bit closer to the date.”

Werner, a professor of Afro-American studies at the University of Wisconsin, and Bradley co-teach a class titled “The Vietnam Era: Music, Media and Mayhem.”

“When we teach our class, we really hammer this with the students from the very first day on, is that there’s no such thing as THE Vietnam vet,” Werner said. “The same songs can mean very different things to different people, but there’s also a piece of it that was shared.” He believes that is summed up by “We Gotta Get Out of This Place”: “That song tended to bring people together.”

Sadler a sensation

Getting out of that place was far from most Americans’ minds in January 1966, when a quick victory in Vietnam was still expected.

That month, they got a symbol of everything that was right about U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Sadler, a clean-cut Special Forces medic who nearly lost his leg after being injured by a punji stick in Vietnam, wrote songs and sang for troops during his recuperation. One of those compositions, “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” was recognized by the brass and RCA as a potential gold mine. It delivered on that promise.

“He kind of went viral 25 years before there was an internet,” said Marc Leepson, a Vietnam veteran, historian and author of “The Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Staff Sergeant Barry Sadler from the Vietnam War and Pop Stardom to Murder and an Unsolved, Violent Death,” which will be published in May 2017.

The album on which the song appeared, “Ballads of the Green Berets,” was recorded in a day and went on to sell 2 million copies. The song, which Robin Moore, author of the novel “The Green Berets,” helped write, sold 9 million copies, spending five weeks at No. 1 and becoming the top single of the year. Sadler appeared in Time and Life magazines and on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Looking back, that success seems unlikely during a year in which the Beatles (“We Can Work it Out,” “Paperback Writer”), the Beach Boys (“Good Vibrations”) and the Rolling Stones (“Paint It, Black”) all spent time at the top of the charts.

In the context of the times, it makes more sense.

“It came out in January of ’66, so the country was pretty solidly behind the Vietnam War,” Leepson said. “There was an anti-war movement, but it was limited to some radicals on college campuses and old-line pacifists and activist leftist groups. It didn’t take over the culture like it would have a year or, at the most, two years after that song.”

Bradley, who was in-country when anti-war sentiment became firmly entrenched, remembers a different reaction.

“It was a joke by the time I was there,” he said. “And (younger troops’ reaction) was pretty derisive, just because, are you kidding me? This guy (Sadler) couldn’t have been here, because he wouldn’t be saying that. ’Cause this is a mess. We’re not gonna win.”

As Bradley and Werner report in “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” “The Ballad of the Green Berets” was widely parodied almost immediately after it was released. They also found, over the course of 300 interviews with veterans, that the song did not age well as attitudes about the war shifted.

“I don’t think we talked to anybody who still likes the song,” said Werner, 64.

Sadler quickly fell out of favor as a recording artist. He cut a couple of follow-up albums, but was unable to duplicate the success of his signature ballad. He had a somewhat lucrative second act in the late ’70s as a writer of military/adventure novels. He later moved to Guatemala and was shot in the head during a mysterious robbery or assassination attempt in 1988. He died in 1989.

Leepson, who points out that the word “Vietnam” doesn’t appear in the song, says despite any lingering feelings some veterans might have, “The Ballad of the Green Berets” endures on oldies radio and in military and Special Forces circles.

“I think today, in 2016, the song is almost completely associated with the U.S. Army Special Forces, the Green Berets. ... It’s played at reunions. It’s played at Fort Bragg (N.C.) all over. … They play it for trainees. They play it at Green Berets’ funerals. So it is a solid part of what the U.S. Army Special Forces is about today.”

The sounds of dissent

As Sadler’s song fell off the charts, the anti-war movement began to rise. The majority of our cultural soundtrack of Vietnam, drawn from post-war movies and TV shows, comes from the rock music that energized that movement. Except the actual soundtrack was much more diverse.

“I think part of what bothers me with the films, in addition to some of what they do with the subject matter and the topic, is that the music almost becomes part of a cliche,” Bradley said. “For me, the soundtrack was deeper and broader and sometimes quieter.”

Although presentations of the war in popular culture tend to lean on message songs, the intent is in the right place, according to music journalist, author and SiriusXM radio talk show host Dave Marsh, 66.

“What they tend to get right is the importance of the music to both the soldiers and to the people back home trying to create a different kind of situation,” he said. “What they get right is the passion … it’s really the passion that the listeners brought to the music and the depth of what they took out of it. I’m not sure, a lot of times, that the performer necessarily understood that it was gonna cut that deep, or the songwriter, either one.”

Songwriters and singers had been part of the protest movement from the beginning. Most of them were folkies associated with the anti-nuclear and civil rights movements such as Pete Seeger, Tom Paxton, Joan Baez, pre-electric Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs. Some songs, such as Dylan’s “Masters of War,” applied in a general sense. Others, like Ochs’ “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” were much more overt.

Protests against U.S. involvement in Vietnam sprang up on college campuses in the early ’60s, and they became more frequent as America’s level of commitment became more public.

The movement built momentum in the latter half of the decade, with major marches in New York and Washington. Heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali refused induction into the Army and was stripped of his title. Martin Luther King Jr. came out against the war, arguing that funding it was depleting social programs.

By early February 1968, a Gallup poll showed that only 35 percent of Americans approved of President Lyndon Johnson’s handling of the war. More violence marred the Democratic National convention in Chicago. Richard Nixon was elected president in November, and the war escalated.

In August 1969, more than 400,000 gathered for the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in upstate New York. Although not explicitly billed as a protest, it was a powerful statement about how far the counterculture had come. The 1970 film that documented the festival gave even wider exposure to two enduring musical statements.

One was Navy veteran Country Joe McDonald’s solo acoustic performance of his “Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” complete with a bouncing ball dancing over its biting lyrics: “Well it’s 1, 2, 3, what are we fighting for? Don’t ask me I don’t give a damn / Next stop is Vietnam.”

The other came courtesy of Jimi Hendrix. Formerly a member of the 101st Airborne Division, Hendrix electrified the crowd with an instrumental version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” awash in chaos and feedback that echoed the sounds of the war. Hendrix, who had played the song live before Woodstock, never stated that it was a protest — although a strong case can be made for that interpretation. It stands as one of the great musical moments of the ’60s, no matter what you take from it.

December 1969 brought the first draft lottery since World War II, a development that made conscription a little more fair but also sparked mass demonstrations. Potential draftees, some just out of high school, were left with tough choices: Vietnam, jail or Canada. Multiple-choice question, without “none of the above” as an answer.

“All wars are tragic, but that was the special tragedy of Vietnam,” Marsh said. “That’s what’s in the music, is the combined vulnerability of people at just the age when they’re supposed to feel invulnerable.”

Nixon’s announcement of a Cambodia campaign in April 1970 sparked a fresh round of campus protests. On May 4, they took a tragic turn at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, when Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of student protesters, killing four.

As the fervor rose, so did the volume.

Some of the most powerful and enduring protest songs came during the Nixon presidency: Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son” (1969); John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” (1969); Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s “Ohio” (1970); Edwin Starr’s “War” (1970); Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” (1971) and John Lennon’s “Imagine” (1971). There were some songs from the other side, although they came largely from country musicians, such as Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee” and “Fightin’ Side of Me.” They weren’t so much pro-war as they were protesting the protesters.

“The music responds to the people. I think that’s what people forget,” Marsh said. “It’s not so much that the music is the voice of the people as it is that the songwriter and the performer must be the ear of the public. Before they can be the mouth, before they can be the voice, they have to listen and find out what’s going on. That’s the difference between Phil Ochs singing ‘I Ain’t Marching Anymore’ and Barry McGuire singing ‘Eve of Destruction.’ One (McGuire’s) is a fantasy, and it tries to be all-encompassing. The other is, very simply, a guy who had to make a decision. That he was not in a very good position to make accurately. One way or another.”

Coming home

Public pressure mounted in 1971 after the publication of the Pentagon Papers revealed that the Johnson administration lied to Congress and the public about the war. On Jan, 15, 1973, Nixon announced that U.S. forces would withdraw from Vietnam within 60 days. The troops were headed home, where they’d need to readjust to the world they left behind.

“They came back and they were basically the same people, except they’d grown up a lot more than you had,” Marsh said. “And the music had something to do with that, I think. Because they had to go deeper into it.”

Music helped veterans process their experiences. Those who served needed more help, though. They needed help getting medical benefits. They also needed help with rehabilitating the image of U.S. servicemembers, who were seen in an unfavorable light by some who blamed the warriors for the war.

In 1978, the Council of Vietnam Veterans — later renamed Vietnam Veterans of America — was formed to address the needs of vets. By 1981, it was broke.

Music again lent a helping hand.

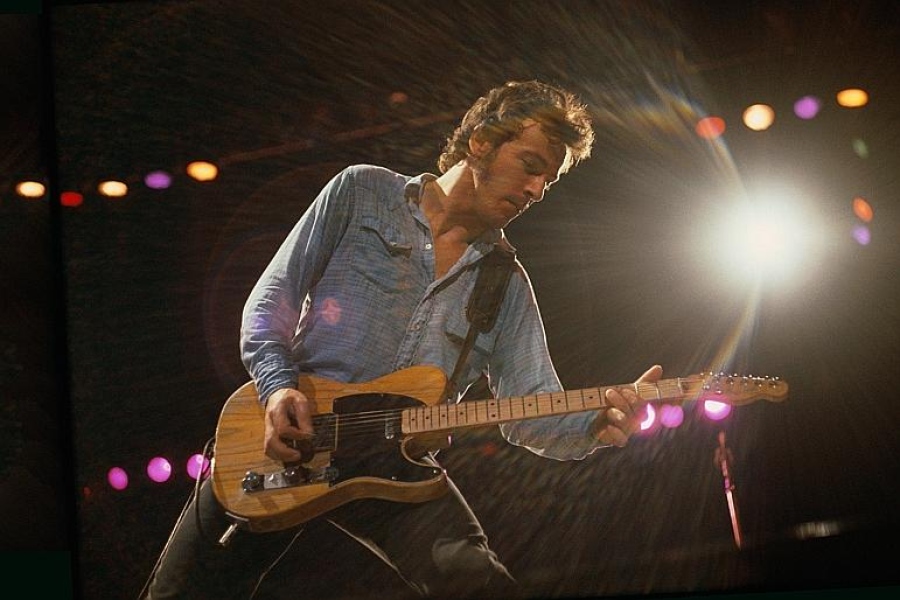

Bruce Springsteen, who was spared going to Vietnam when he failed his Army physical, had been directly affected by the war when the drummer from his garage band was killed there. He became interested in the plight of veterans while reading Ron Kovic’s memoir “Born on the Fourth of July,” and was inspired to act after meeting Kovic. Springsteen reached out, through his management, to VVA co-founder and president Bobby Muller.

“We were hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt,” Muller told Bradley and Werner in an interview for “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” “I’m in my [New York] office and I’m preparing to close down the organization [and] I get a call.”

That call led to a meeting with Springsteen. The meeting led to a sold-out benefit Aug. 20, 1981, at the L.A. Memorial Sports Arena. It also led to a $100,000 check from Springsteen to the VVA.

“Unless we’re able to walk down those dark alleys and look into the eyes of the men and women that are down there and the things that happened, we’re never gonna be able to get home,” Springsteen told the audience that night.

He has remained true to those words.

“The face of rock and roll, on this issue, from the beginning, has been Bruce Springsteen,” said Marsh, who has published four books about Springsteen. “And there’s a (Vietnam) song on his last album, ‘High Hopes,’ (called) ‘The Wall.’ So it’s still on his mind. … I think it’s just like the Marines; you don’t leave casualties behind. You don’t turn your back on somebody.”

The troops got out of that place. For some, it was the last thing they ever did. Through Springsteen’s contributions, the survivors continue to be helped by “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” just like they were in-country. Again, The Animals and the song’s writers could never have anticipated its reach.

Springsteen described its lasting influence during his keynote address at the South by Southwest Music Conference on March 15, 2012, in Austin, Texas.

“To me, The Animals were a revelation,” he said. “The first records with full-blown class consciousness that I’d ever heard.”

He then picked up an acoustic guitar and played the first verse and chorus of “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” Putting the guitar down, he said, “That’s every song I’ve ever written. That’s all of ’em. I’m not kiddin’, either. That’s ‘Born to Run,’ ‘Born in the U.S.A.’, everything I’ve done for the past 40 years.”

‘A great moment’

The musical influence of the Vietnam era stretches beyond Springsteen. In the most literal sense, future musicians will continue to be influenced by those of the ’60s. A band that hasn’t even formed yet will one day make its “Revolver.” The activism carried over, too, in the form of benefit concerts. GIs continue to consume music in a very personal way. The difference is that technology, which helped create the shared soundtrack of the Vietnam War, gave troops more choices. In gaining the ability to personalize their war experience, they lost the sense of community.

“Doug (Bradley) and I were in Montana a couple of years ago, and we were at a VFW club doing a soundtrack, or what we called the Vietnam Jukebox,” Keesing said. “And we asked some of the younger vets who had been to Iraq and Afghanistan and Desert Storm/Desert Shield whether there were any songs that had the same kind of meaning as ‘We Gotta Get Out of This Place.’ Was there one song, or were there a handful of songs that every vet from the more recent conflicts would know, and the answer was no. Because they’re now able to download and put on their iPods or whatever the songs that they like.”

Despite its lasting effects, the soundtrack of the Vietnam War is unique. It was created at a special time, when technology, sociology and history converged. Music tied them together in a way they had not been connected before or since. That particular set of creative circumstances might never come around again.

“It’s also just a great moment in musical history, which isn’t an accident. That’s not just nostalgia,” said Werner, whose other music books include “A Change is Gonna Come: Music, Race and the Soul of America.”

“It’s really the first time that rock, country and soul are talking to each other, and everybody was hearing all of that. You didn’t have to love Johnny Cash to know who Johnny Cash was. You didn’t have to love James Brown to know who James Brown was, and all the musicians were all listening to each other. Sam Cooke writes ‘A Change is Gonna Come’ in response to (Bob Dylan’s) ‘Blowin’ in the Wind,’ and back and forth. … So it’s a really interesting moment, and that just isn’t the case anymore. The younger vets and younger people have all had 97,000 different kinds of music that they can listen to, and they make their own choices. And those musics aren’t talking to each other in the same way.”

JOEL BERNSTEIN/COURTESY OF SHORE FIRE MEDIA