This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

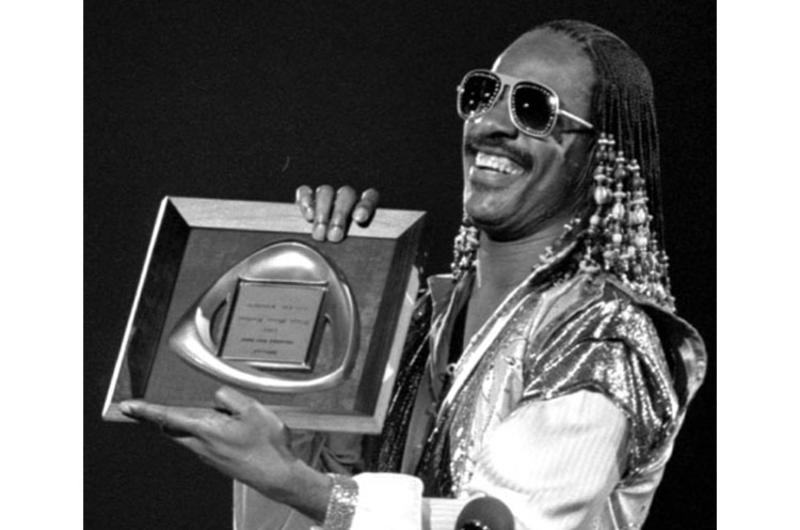

`Stevie, touch me!' — A feel for people, too

Stevie Wonder, at the 10th annual Tokyo Music Festival in 1981.

By Hal Drake | Stars and Stripes April 7, 1981

TOKYO — "Stevie, please touch my face," the tall fashion model pleaded through the crowd noise. "You'll remember me. I was 14. It was in Portland."

Fourteen she might have been, but now she was lissomely mature, long out of gawky adolescence. Stevie Wonder turned and ran fingers that were like sensitive calipers down her cheeks and nose.

"Oh, I love you, I love you," she said, squeezing Wonder in an impulsive hug.

"Thank you," Wonder replied in a tired, on-the-road voice. Then he made his way through the crush in the ballroom of the Tokyo Prince Hotel, where he had just held court for some of the hundreds who would watch him at the 10th Tokyo Music Festival.

Unlike the legendary blind man who can reach out and recognize more faces than an Irish politician, Wonder said, he doesn't have instant fingertip recall.

"TO BE HONEST, straight up. There wasn't enough time for me to say, 'Hey, I know who she is,' " Wonder said. "But I know I've met her before and I know that, most importantly, the meeting of her again and the fact that the connection happened again is special enough for me."

The connection, that special touch of spiritual warmth, the sudden handshake and tight hug from strangers in a crowd, the fingers on the face. It flows through Stevie Wonder's feelings and music, all he plays, composes or sings.

It has happened in Portland, Denver, Tokyo and Detroit — first in that last place, when Steveland Morris was a junior deacon in a Baptist Church and looked toward a career in the ministry.

That was before he knew about Motown, he related. "At 11, I was wanting to get some money (by getting into music) — no, I'm kidding you — but it (the ministry) was something I wanted to do," he said.

"I wanted to be a doctor, too. Just as bizarre back then, but now that's become a reality, too — having a few blind doctors in the States now."

But that early career dreaming was before that first connection, the one that made the Impossible Dream come true.

"I'VE ALWAYS liked music, for sure," Wonder said. "But I didn't know I was going to have my name changed — although I did have a dream that a disc jockey in Detroit was playing a record, and it was about the same tempo of the song that really was released when I did become an artist."

"I Call It Pretty Music," Wonder said, was the song he dreamed of. It would be one of the songs in a fabulous flow of success.

At the Budokan (Hall of Martial Arts) the night of the festival, Stevie Wonder, ringed in spotlights that were like luminous snares, was rolled to center stage.

"You Are the Sunshine Of My Life" was one of the starters.

The trolley-beat handclapping kept time, then broke into applause.

That voice is an old master's one-of-a-kind instrument, going from low croon to mellow roar.

HE WHO GIVES, gets. As the piano was rolled back, Stevie Wonder rode buoyantly on the applause, looking like a figure on the rear platform of an outgoing train.

Yea, though the ministry made way for Motown, Stevie Wonder, like many artists, is still sometimes beset by the Pharisees.

Critics.

A lot of them didn't like "Journey Through the Life of the Plants," cosmic "think stuff" that sold a million albums in America and quickly cleared the shelves in Europe.

"I basically say a lot of critics are frustrated musicians ..." Wonder smiled. "They stereotype and categorize, and they say, "Well, this is what is supposed to be."

"What happens when it's something different — it's like brushing their feathers. 'Oh, my God, it's supposed to be over here; it's not supposed to be over there.' "

WONDER SAID that while he was working on far-out stuff in "Plants," he gave one of his more conventional songs to Jermaine Jackson so that people wouldn't think he'd abandoned his bread-and-butter fare.

"It was called, 'Let's Get Serious,' a kind of uptempo rhythm and blues pop song and I was happy with it," Wonder recalled.

"... I really wanted to (record) it myself."

Then he thought: What about those critics, the ones who would write, "Oh, my God, what's happened to Wonder? He's gone nuts. He thinks he can talk to plants now."

"And what happened, I said, 'I'll give this sucker to him, I'll will this song to Jermaine.' People will know there's still this other (not-so-far-out) vibe."

Despite that concession to critics, Wonder said, he could care less about them.

"You know, I don't mind, it really doesn't bother me," he said of the printed barbs. "I've become kind of amused by the various things written about me."