This website was created and maintained from May 2020 to May 2021 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Stars and Stripes operations in the Pacific.

It will no longer be updated, but we encourage you to explore the site and view content we felt best illustrated Stars and Stripes' continued support of the Pacific theater since 1945.

The cost of newsgathering

Associated Press photographer Horst Faas stands in front of AP's Saigon bureau as a burned out tank smolders in the street. Most likely taken in the aftermath of the coup, in Saigon on or about November 1, 1963.

The following is an edited version of a column written by former Stars and Stripes senior reporter Hal Drake and published in October 1995.

Pacific Stars and Stripes has lost two reporters in two wars — one a 37-year old veteran, the other a youngster only 24. I knew one only slightly and the other not at all.

I called the home of Ernie Peeler's son in California not long ago, wanting to know as much as he might remember about his dad — the reporter we lost in the hard and early days of the Korean War.

Gone before my time, he was a man I never knew, except by reputation and the quality of work I found in a few faded library clippings.

I learned Peeler had been an International News Service reporter and could believe that because of his neat, tight writing, the kind required by telegraphic news services. During World War II, he had worked in military information offices, which ideally qualified him for Stripes — a guy who knew the business from both ends of the telephone.

He was good and he was gutsy, this Peeler — the kind of reporter who would stand fire to get his story, walking into enemy cylinders of every caliber millimeter.

Peeler and Hal Gamble were the first Pacific Stars and Stripes reporters sent to cover the war, which broke over the benign occupation life in Japan like a storm over a picnic. Within days, the two were of Tokyo and in Korea, reporting a difficult and confusing conflict.

Peeler took chances — a lot of chances. Good reporters always do, taking a soldier's chances to do a newsman's job.

So it was July 28, 1950, when he was declared missing in action — perhaps slain by an enemy tank that blew his Jeep off the road. Old-timers at Stripes told me of hopefully scanning POW lists provided by the Communists at Panmunjom. Ernest never turned up.

On the day he disappeared, Peeler was out of hostile range when he and Ray Richards, an International News Service correspondent, decided to head north, toward a broken, disorganized nonentity called the front, to get "just a little more" before they wrote their stories — a decision that can cost a reporter's life.

But the good ones do it.

There was another man I scarcely knew, and wish I had known better.

Two decades have gone by since the last shot in Saigon, but I can't forget the most hurtful happening of a long-ago war — the loss of Paul Savanuck.

Why can't I scrub my memory of a 24-year old kid I hardly touched hands with?

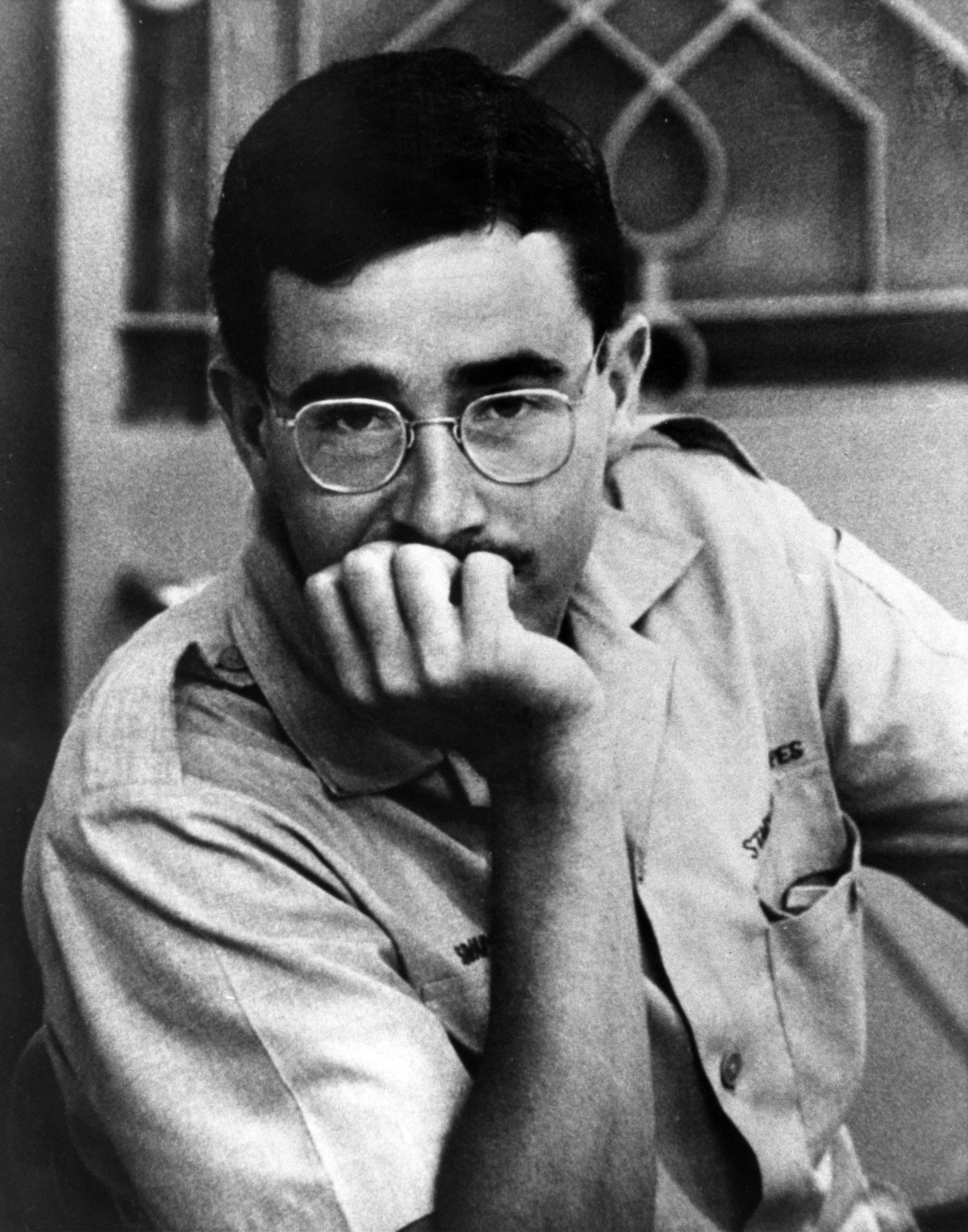

He was like a face on a passing streetcar or casual acquaintance at a bit party. A quiet kid — one of those who could sit in a crowded room for four hours without saying a word. Bespectacled and absently preoccupied, he was remindful of a student for the priesthood or rabbinate.

His constant expression was a thoughtful frown — the one he wore that day in early 1969 as I walked into the Pacific Stars and Stripes Saigon Bureau with colleague Al Kramer, sent from Tokyo to do a special supplement on the war.

The bureau of Vo Tanh Road was a bizarre place, manned by youngsters who lived in the age of Aquarius and Zumwalt. It showed. The walls were done over in psychedelic rainbow, along with pungent lyrics from the rock musical "Hair" and pinups that would have sent a chaplain into convulsive shock. Our people were called the Wild Bunch, and not without reason.

All except Paul Savanuck, who was a few days new to the bureau and had a discomfited look, like a chaplain's assistant who was trying to be one of the guys but still blanched at a dirty joke. As we met, all I got was a loose handshake and a mutter.

Oh no, I thought. Was this another anti-Vietnam draftee, not here to report the war but to protest it? The indiscriminate draft had dumped all manner of characters on us, and the last thing we needed was another Greenwich Village poet posing as a reporter.

I spoke these fears aloud, in private, to Dave Walsh, a Navy journalist attached to the bureau.

"No, Hal," Dave assured me. "He's a shy sort, doesn't like to push himself. He's new here, hardly been around a week — just feeling his way around. Give him time. He'll open up."

Bureau Chief Bill Collins told me Savanuck had volunteered for both Vietnam and Stripes, aggressively pounding on the door until Bill granted him a tryout and nodded him in. His diffident manner belied that. Again, I was told — give him time.

There was a drowsy afternoon we were all sitting around, with Savanuck right beside us but a hundred miles away under a canopy of mood. Mike Kopp, a bureau photographer, had a new Nikkormat and was trying it out on anybody who would hold still for five seconds. Savanuck was staring at our well-sized battle map.

"Hey, Paul," Kopp said. "This way."

Startled, Savanuck absently jerked around and put his chin on the heel of his hand, looking like that classic statue of The Thinker. We would have that, at least — a picture that caught perfectly the subtle and introspective character of Paul Savanuck.

A day or so later, he was gone, headed up country to cover the war.

Then came that gloomy morning.

There had been a rowdy party at the bureau the night before. Master Sgt. Bill Bradford, the first shirt, expressed bitter regret that a can of beer and the contents of a wastebasket has been flung into an overhead fan. He stood by, in a surly posture with his hands on his hips, while we meekly mopped up the mess. Lt. Col Sal Fede, the officer in charge, waling in with a stormfront over his face. Having just borne Bradford’s wrath, we braced for Sal's.

Sal walked over to Collins and spoke in a confidential tone that still carried: "Savanuck's dead. He bought it last night up at Quang Tri."

There was more boozing that night, but it was morose and depressing. To Dave Walsh fell the stressful job of going up to a remote corner of the Marine base at Da Nang and walking under a sign that read: "In Reverence — Uncover." Dave nodded as an attendant lifted a rubber wrapping from a still form.

Not long after, Dave was in Tokyo and he and I toured the Kanda district that abounds with bookstores. It also had the oldest beer hall in Tokyo, we and stopped to pay proper respect to a cultural landmark.

After a time, Dave looked absent and thoughtful much like Savanuck, and said: "Jesus, that was awful about Paul. If he'd just been around a little longer and gotten to know you and Kramer and all the guys, he'd have opened up. He was a nice kid."

I wept a little, for somebody I hadn't known very well for very long.

I could never feel like Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Savanuck, but I still felt sadly deprived.

Michael Kopp/Stars and Stripes